Social groups and communities. Classification of social groups. Social groups, their classification Concept meaning and classification of social groups

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

STATE BUDGET EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION OF HIGHER PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

"URAL STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY" OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Independent work

Classification of social groups

Completed by: Kosenkova Maria Igorevna

1. Social group

A social group is an association of people who have common significant specific characteristics based on their participation in some activity connected by a system of relations that are regulated by formal or informal social institutions.

2. Classifications of social groups

The first classification is based on a criterion (character) such as number, i.e. the number of people who are members of the group. Accordingly, there are three types of groups:

1) small group - a small community of people who are in direct personal contact and interaction with each other

2) middle group- a relatively numerous community of ideas that are in indirect functional interaction.

3) large group - a large community of people who are socially and structurally dependent on each other.

The second classification is associated with such a criterion as the time of the group’s existence. Here are the highlights:

1) short-term

2) long-term

The third classification is based on such a criterion as the structural integrity of the group. On this basis they distinguish:

1) primary

2) secondary groups.

A secondary group is a collection of primary small groups.

3. The main ways of forming social groups are the following

· employees come to understand that achieving certain goals is possible only on the basis of connecting, combining the efforts of a certain number of members of the organization;

· during labor activity individuals require the understanding and support of work colleagues, for which he selects individual members of the organization with whom not only business, but also trusting relationships are possible;

· in the process of identification, some of the members of the organization develop a feeling of an ingroup, which in turn leads to the formation of a system of closer connections, the separation of this ingroup from the rest of the organization members, and the drawing of group boundaries;

· some workers need to protect their interests and needs, which is possible only by combining efforts in the conditions of the organization, including the individual in social institutions that also carry out their functions through the activities of organizations;

· individuals need control over basic norms of behavior, since they have a need for social order and maintaining stable social relationships;

· all individuals have a need to communicate and spend free time with colleagues, which can only be realized within a social group.

4. Types of groups

There are large, medium and small groups.

IN large groups includes aggregates of people existing on the scale of society as a whole: these are social layers, professional groups, ethnic communities (nations, nationalities), age groups (youth, pensioners), etc. Awareness of belonging to a social group and, accordingly, its interests as one’s own occurs gradually, as organizations are formed that protect the interests of the group (for example, workers’ struggle for their rights and interests through workers' organizations).

TO middle groups include production associations of enterprise workers, territorial communities (residents of the same village, city, district, etc.).

Toward the diverse small groups include such groups (up to 15 people) as family, friendly companies, and neighborhood communities. They are distinguished by the presence of interpersonal relationships and personal contacts with each other.

One of the earliest and most famous classifications of small groups into primary and secondary was given by the American sociologist C. H. Cooley, where he distinguished between them. "Primary (core) group" refers to those personal relationships that are direct, face-to-face, relatively permanent, and deep, such as relationships within a family, a group of close friends, and the like. "Secondary groups" (a phrase that Cooley did not actually use, but which came later) refers to all other face-to-face relationships, but especially to groups or associations such as industrial ones, in which a person relates to others through formal , often legal or contractual relationships]. Social groups are friendly interactions. There are many groups of people uniting, each with a common cause and a common goal.

5. The main provisions of the theory of social exchange

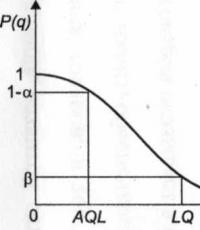

The basic theoretical formulations, based on the assumption that behavior is a function of consequences and associated rewards and punishments, were developed by Homans in 1961 and refined in 1974. They include five main provisions:

1. “Provision for success.” The more often an activity is rewarded, the more likely it is to occur. Behavior that produces positive consequences for an individual is very likely to be repeated.

2. “Incentive Clause.” Similar circumstances or similar situations will stimulate behavior that has been rewarded on similar occasions in the past. This allows generalization of behavioral reactions to “new” situations.

3. “Statement of Value.” The more valuable the results of an action are to the actor, the more likely it is that the action will be performed.

4. “The deprivation-satiation clause” introduces the general idea of reducing marginal utility (utility). The more often a person has received a particular reward for an action, the less valuable the additional element of that reward is. Thus, some rewards become less effective, leading to the curtailment of some specific activities. True, this position is less true in relation to generalized generalizations, such as money and feelings (affections), or anything else where saturation is less likely to happen, except in extreme cases.

5. “Statement on emotionality.” It's about about the conditions under which people respond emotionally to various rewarding situations.

6. Urlevels of social group development

The level of development of a social group is a qualitative stage that characterizes its socio-psychological maturity. The group develops along a continuum - starting at the lowest level, going through several stages and reaching the highest level.

In Russian psychology, there are several classifications of levels of group development. Thus, E. S. Kuzmin distinguishes three levels:

1. Nominal group.

2. Cooperation.

3. Team.

N. N. Obozov divides the development of the group into four stages:

1. Diffuse group.

2. Association.

3.Corporation.

4. Team.

L.I. Umansky takes an even more differentiated approach to this classification and identifies six levels;

1.Conglomerate

2.Nominal group

3.Association

4.Cooperative

5.Autonomy

6. Team

Taking as a basis the classification of L. I. Umansky as the most developed and tested in practice, we will describe the levels of the developed group, based on three main criteria:

Common goals joint activities;

Clarity of group structure;

Dynamics of group processes.

Based on these criteria, the socio-psychological maturity of the group can be characterized.

A conglomerate (lat. conglomerates - collected, accumulated) is a group of previously unfamiliar people who found themselves in the same territory at the same time. Each member of such a group pursues his own individual goal. There are no joint activities. There is also no group structure or it is extremely primitive. Examples of such a group include a small crowd, a line of passengers in a train carriage, a bus, an airplane cabin, etc. Communication here is short-lived, superficial and situational. People, as a rule, do not get to know each other. Such a group easily breaks up when each participant has solved their individual problems.

7. Real and nominal groups

A nominal group (lat. nominalis - nominal, existing only in name) is a group of people who have gathered together and received common name, Name. For example, applicants admitted to a university gather on the first day of classes and are named a freshman group. In production, the shop manager can gather newly arrived workers and explain to them that they are a team of repairmen. Such a name for a group is necessary not only so that it receives official status, but also in order to determine the goals and types of its activities, mode of operation, and relationships with other groups. Thus, the activity of a team of repairmen is a service activity, serving the activities of other groups of workers who perform the main work of producing products.

A nominal group can remain a conglomerate group if the people gathered together do not accept the proposed conditions of activity, the official goals of the organization and do not enter into interpersonal communication. In this case, the nominal group disintegrates. But if the goals and conditions are clear and people agree with them, then the nominal group begins to begin activities and the next level of development rises. Therefore, a nominal group is always a short-term stage of group formation. Its characteristic feature is that in order for a group to become nominal, an organizer is needed - one person or an entire organization that would bring people together and offer them goals for joint activity. The main thing that members of a nominal group do is communicate, i.e. getting to know each other and the goals, methods and conditions of upcoming joint activities. Until the activity itself begins, but the process of discussion and agreement is underway, the group will be nominal. As soon as people start working together, the group moves to another level of development.

A real group (in social psychology) is a community of people unlimited in size, existing in a common space and time and united by various kinds of real relationships (for example, a school class, a work team, a military unit, a family, etc.). The largest in size G. river. humanity is a historical and social community, united, despite all the differences between countries and peoples, by economic, political, spiritual and other ties. Smallest G. r. is a dyad, i.e. two interacting individuals.

8. Small and large social groups

Large groups include aggregates of people that exist on the scale of society as a whole: these are social strata, professional groups, ethnic communities (nations, nationalities), age groups (youth, pensioners), etc. Awareness of belonging to a social group and, accordingly, its interests as one’s own occurs gradually, as organizations are formed that protect the interests of the group (for example, the struggle of workers for their rights and interests through workers’ organizations).

Diverse small groups include groups (up to 15 people) such as family, friendly groups, and neighborhood communities. They are distinguished by the presence of interpersonal relationships and personal contacts with each other.

§ small, where a small number of members provides the opportunity for constant, direct personal mutual influence and therefore there is no need for mandatory formal reinforcement of institutionalized rules of behavior;

§ big(large), where there is no possibility of constant direct personal interaction, therefore, when describing them it is impossible to do without some kind of abstraction.

9. Designed andinformal social groups

In organizationally unformed parties there is no membership, and therefore no formal connection between the party’s organs and its supporters. These are considered voters who vote for a party in elections. Naturally, they do not have documents confirming party affiliation, do not pay party dues and are not required to submit to party discipline. The party apparatus, consisting of professionals and activists, operates mainly during the election campaign. These parties are essentially electoral movements.

Organizationally designed political parties usually small in number of members, but have a clear organization and discipline. They are also called personnel parties. The basis of these parties is a professional centralized apparatus. The central leadership, headed by the party leader, has the final say in all party affairs. A group of senior party leaders meeting for preliminary discussions on political and organizational issues and actually predetermining the decisions of the relevant party forums, in English-speaking countries is called a caucus. In such parties, there is an organizational connection between the party bodies and its members, who have party cards, are required to obey the statutory requirements and pay monthly or annual party dues (rarely more than 1% of income). Membership in such parties is possible both individually and collectively.

10. Groupsmemberships and reference groups

Referent (standard) - troupes, determined by the degree of consciousness of the attitude of individuals towards them. This is a real or conditional social community with which the individual relates himself as a standard and to whose norms, opinions, values and assessments he is guided in his behavior and self-esteem.

The reference group performs two important functions.

The normative function is manifested in motivational processes. The reference group acts as a source of norms of behavior, social attitudes and value orientations of the individual.

The comparative function manifests itself in the processes of social perception (social perception). The reference group acts here as a standard by which the individual evaluates himself and others

Reference groups can be both “positive” and “negative” in an individual’s mind.

“Positive” are those with which the individual identifies himself and of which he would like to become a member.

“Negative” reference groups include those that cause rejection in the individual.

Each individual may have a different number of reference groups depending on the types of relationships and activities. Situations are possible when the reference groups for an individual have oppositely directed values, which can lead to the formation of serious intrapersonal conflicts that require psychological or psychotherapeutic counseling.

It was experimentally established that some members of small groups share the norms of behavior not of their groups, but of others, to which they are guided, although they are not represented by their membership in them. For the first time, the division of groups into reference and membership groups was introduced by G. Hyman.

Membership groups are groups in which the individual is not opposed to the group itself, and where he relates himself to all other members of the group, and they relate themselves to him.

11.Temporary and permanentsocial groups

Permanent social groups include social classes (rich, poor).

Temporary groups can exist from a few days (a group of students on vacation) to several decades (a cartel of workers).

12. Natural and laboratory social groups

Natural groups are those that form on their own, regardless of the desire of the experimenter. They arise and exist based on the needs of society or the people included in these groups.

In contrast, laboratory groups are created by an experimenter for the purpose of carrying out some scientific research, testing the hypothesis. They are as effective as other groups, but exist temporarily - only in the laboratory.

13. Normative behavior and group behaviorI cohesion of social groups

Secondary groups arise to implement certain general social goals. For example, uniting scientists into associations or politicians into political parties. In these groups, material contacts, most often indirect, are of particular importance. They rely on an institutionalized and schematized system of relations, their activities are regulated by norms and rules.

Most sociologists associate the concept of a “secondary group” with large associations of people, for example, territorial communities, whose normative behavior and group cohesion are regulated by social interests.

At the level of the emergence and functioning of a group, the determining factors are individual interests and needs, the satisfaction of which requires collective efforts, and therefore interpersonal interactions. Contacts of group members and their mutual influence can be represented in the form of a structure of relationships. For example, group member A interacts with B and C. It is assumed that as a result of interactions, a certain group structure develops, in which each group member takes “his place”, regardless of what tasks the group must solve.

There are three possible models for such interaction.

Satisfaction with group relationships is highest in a multi-channel model, lowest in a circular design, and mixed in a centered design, where the central figure may experience great satisfaction and people in positions around her may feel isolated.

Group interactions are mediated (usually) by normative behavior, sometimes called a pattern. It is associated with the implementation of the group’s goals and is recognized to one degree or another by all representatives of the group.

Very often, group interactions are identified by sociologists with the concept of group structure, since they are associated with other elements: role and status. Considering the significant share of normative regulation among other manifestations of social influence in a group, there is reason to consider normative behavior as an independent factor].

The diversity of group norms and the factors that determine them allows us to identify general methodological principles for the effectiveness of norms in small groups.

1. Social norms of group behavior are a product of social interaction between people united by common interests.

2. As a rule, the group does not establish the entire range of norms for any specific situation, but only those that are of particular significance for all members of the group.

3. Normative behavior can either be prescribed to a group member in the form of a role (for example, leader), or act as a role standard of behavior common to group members.

4. Social norms can be differentiated by the degree of their acceptance by group members: approved by all, part, etc.

5. Social norms in groups may have different continuums of deviations and, accordingly, ranges of sanctions for deviant behavior.

6. The level of recognition of group norms by all group members largely determines the nature of group cohesion

14. Social and psychological hacharacteristics of the established group

The richness of the phenomenology of the group process, clearly revealed in the course of the previous presentation, makes the choice of characteristics of the existing small group by no means simple. This chapter examines three of them, which, in our opinion, best give an idea of the group from the point of view of its holistic manifestations: the structure of the group, the norms functioning in it, group cohesion. It is the level of development of these kind of parameters of the group process that often, as shown in 2.2, gives researchers the basis to judge the level of group formation as a whole.

15. Social and psychological components of organizational culture

At the heart of the formation unified system An organization's values are based on a number of principles. Values as a key element of organizational culture.

Principles:

1. The principle of consistency - predetermines the consideration of the culture being formed as a system of interconnected elements, change (improvement) which is possible only through changes in each element.

2. The principle of complexity - consists of considering culture taking into account the influence of psychological, social, organizational, economic, legal and other factors.

3. The principle of nationalism - when forming culture, it provides for taking into account national characteristics, mentality, customs of the region, country in which the organization is located and operates.

4. The principle of historicity - determines the need for the system of values of the organization and the practice of interpersonal relations to correspond to fundamental modern human values, as well as taking into account their dynamics over time.

5. The principle of scientificity - presupposes the need to use scientifically based methods in shaping the culture of the organization.

6. The principle of value orientation is the principle of the basic guiding role of the value system for the entire organization as a whole.

7. The principle of scenarios - provides for the presentation of all recommendations, acts that define and regulate the relations and actions of the organization’s personnel in the form of a scenario that describes the content of the activities of all its employees, prescribes for them a certain character and style of behavior.

8. The principle of effectiveness - presupposes the need for targeted influence on the elements of the organization’s culture and its attributes in order to achieve the best socio-psychological conditions for the activities of the organization’s personnel and increase the efficiency of its activities. See: Sukhorukov M. Values as a key element of organizational culture.

It is necessary to add to the list of important ones the principle of the formation and reproduction of values, specifically in a Russian organization - the principle of personal loyalty.

social psychological group organizational

16. Characteristics of a social group at a diffuse level of development

In a diffuse group there is no cohesion, no organization, and no joint activity. An important indicator of the level of development of a group is value-orientation unity, determined by the degree of coincidence of the positions and assessments of its members in relation to the general activities and important values of the group.

Groups are considered from the point of view of their attitude towards society: positive - prosocial, negative - asocial.

Any team is a well-organized prosocial group, since it is focused on the benefit of society.

A well-organized asocial group is called a corporation.

Posted on Allbest.ru

Similar documents

Principles of the socio-psychological approach to the study of social groups. Characteristics of groups and their impact on the individual. Scientific approaches to group classification. Levels of group development: conglomerate, association, cooperation, autonomy, corporation.

abstract, added 03/02/2011

Primary and secondary, internal and external, formal and informal, reference social groups. Dynamic characteristics of social groups, main features and functions of group community. Groups as objects of socio-psychological analysis.

test, added 03/16/2010

The concept of a small group, its characteristics and boundaries. Definition of a social group, typology of social groups. Concept and classification of political regimes, characteristics and their main features. Definition and characteristics of the main types of social communities.

test, added 06/28/2012

Self-help groups are voluntary associations of people to jointly overcome illnesses, mental or social problems. Rules and methods of group activity. Types of self-help groups and their characteristics. Therapeutic factors of self-help groups.

abstract, added 08/10/2010

Social group as an individual’s living environment. Characteristics of small social groups, their classification according to the degree of organization, the nature of intra-group interactions. The concept of internal and external groups. Dynamics of small social groups.

test, added 02/13/2011

Characteristics of sociology as a science about the laws of development and functioning of social communities and social processes. The question of the fundamental position of the theory of social exchange. Determination of the position occupied by an individual in a large social group.

test, added 08/20/2011

The concept of poverty as a characteristic of the economic situation of an individual or group. Characteristics of the social group of the poor. Features of methodological approaches to measuring poverty. Analysis of the structure of the social group of the poor in the Russian Federation.

abstract, added 11/24/2016

The essence and main characteristics of a social group. Large, medium and small groups, their characteristics. The concept of formal and informal social groups. Social communities and their types. Social institutions as forms of organization of social life.

presentation, added 03/17/2012

The concept of a social group in sociology. Typology of social groups. Small, medium and large social groups. Signs and characteristics of social organization. Formal and informal social organizations. The concept of social community in sociology.

abstract, added 08/17/2015

What is a social group? Forms of social communities and social control. Role, structure, factors of functioning of social groups. Group dynamics. Methods of communication in groups of five members.

A social group is an association of people based on some significant social characteristic. Participants in such associations may engage in common activities, have a certain structure of relationships, or be in the same conditions. Members of the group, one way or another, are aware of their involvement in this formation.

Sociology and social psychology study social groups.

The group is very diverse. First of all, there are small, large and medium groups.

The larger group is ethnic communities, and so on.

As part of the study of averages, teams working at enterprises and residents of one city or region are considered.

Small groups include family, groups of friends, etc. Distinctive feature These are the presence of contacts and interpersonal or emotional relationships of their participants with each other. Much of the research in social psychology focuses on small groups.

Groups can be based on various characteristics.

For example, primary and secondary are distinguished. Primary are characterized by the presence of direct contacts between participants. In secondary ones, special means are used for communication, for example, various kinds of messages. Members of the secondary group are more separated from each other.

There is also a classification of social groups based on how clearly the status of each member of the association is defined. Based on this, small groups are divided into formal and informal. The first type is characterized by a fixed role system. The form of leadership and subordination is also strictly fixed. Informal groups develop spontaneously; sometimes they can arise within formal associations. If within an informal group there appears general activities, then a fairly clear structure may emerge.

Another classification of social groups is based on whether a person participates in groups that are significant to him. From this point of view, two types are distinguished.

A membership group is an association of which a person is a member.

The reference social group serves as a certain standard for the individual, a source of social norms and values, however, he is not always a member of it.

From this point of view, reference groups can be divided into ideal and presence groups.

The ideal group can be either real or fictitious. The main thing is that the person does not participate in it, and the accepted value system is especially attractive to him.

Reference groups are also divided into positive and negative.

If an individual fully shares and supports a positive group, then the norms adopted in a negative group are perceived negatively. At the same time, the values of both groups have a significant influence on a person.

In order to clearly show the mechanism of the influence of group opinion on consciousness, we will give examples of social groups whose value system is perceived positively.

Thus, for a teenager, a positive reference group may be a group of high school students whose opinions are important to him. He strives to imitate them, wears the same clothes, listens to music that these high school students like.

Also, for a young person, the reference group may consist of individuals belonging to completely different associations. For example, father, movie hero and coach.

In this case, each of them has certain traits that are valued by a teenager. It could be courage, boldness or independence.

The classification of social groups allows us to study the mechanisms of influence of society's norms on a person, thanks to which we can find out the reasons and patterns of people's behavior. The information obtained can be used in a variety of areas, for example, to clarify the mechanisms of formation of addictive behavior, as well as to establish patterns of interaction between people in teams.

Topic 10. Psychology of social groups

Large social groups

Mass communication

Social psyche

Small social groups

Classification of small groups

Group dynamics

Small group development

Interaction between an individual and a small group

Conformism and compliance

The effects of polarization and grouping of thinking

Deindividuation

Leadership and Guidance

Review of Leadership Theories

Leadership and management in small groups

Leadership, management, power

Leadership styles

Characteristics of leader qualities

How to become a leader

Classification of social groups

When there are two or more people interacting with each other or being aware of each other's presence, we can already talk about a group. Typically, group members have a common goal.

Group - two or more persons who interact with each other, are aware of each other's existence, and have a common goal.

The Teacher’s Psychological Handbook (L.I. Fridman, I.Yu. Kulagina) provides the following definition of a group:

“A group is a certain collection of people, considered from the point of view of social, industrial, economic, everyday, professional, age, etc. community."

In social psychology, there are many classifications of groups built on different bases:

Method of education

Organization and type of leadership,

Tasks and functions,

The predominant type of contacts in the group,

State of the art,

Principles of accessibility of group membership,

Size (number of members),

First of all, for social psychology, the division of groups into conditional And real.

On the one hand, in practice, for example, demographic analysis, in various branches of statistics, we mean conditional groups: arbitrary associations (groupings) of people according to some common characteristic necessary in a given system of analysis.

On the other hand, in the whole cycle of social sciences, a group is understood really existing education, in which people are brought together, united by one common characteristic, a type of joint activity, or placed in some identical conditions, circumstances, in a certain way aware of their belonging to this formation.

Social psychology focuses its research on real groups.

Real laboratory groups - predominantly appear in general psychological research.

Real natural groups are formed under natural conditions. These include big(nations, trade unions, social classes, gender and age groups, etc.) and small social groups (student group, sports team, family, work team, etc.).

In general, the classification can be clearly presented in the following diagram (Fig. 10.1).

Obviously, each person interacts with a variety of groups. People constantly need each other and rely on each other. Some groups rely on formal, strictly defined rules, such as political parties, trade unions, sects, whose activities are based on very specific goals. However, there are others, more informal groups, such as family, your friends, buddies with whom you interact constantly.

Some groups have a leader, others can do without one. Indeed, spectators in a cinema, shoppers in a store, or passengers waiting for a train do not need a leader, while an orchestra or a group of students, as a rule, need a leader.

Regardless of whether the group has a leader or not, any group is characterized by dynamics, i.e. is constantly changing and people, interacting with each other, change their attitudes and behavior under the influence of the group.

Large social groups

Under large social group is understood as a certain social reality that goes beyond the consciousness of the individual and affects his psyche. This is an objective factor influencing the individual’s psyche.

If a small group is a microsystem, then a large group is a macrosystem.

Examples of large social groups are:

State,

Nationalities,

In addition, there are gender and age groups (youth, pensioners, women, men) that have specific psychological traits. It is also possible to distinguish people living in different geographical latitudes, for example, it is known that northern peoples are more stern, reserved, and slow, while southern peoples are emotional, relaxed, and sociable.

These are groups that arose during the historical development of society, long-term, sustainable in its existence.

Spontaneously formed groups - these are fairly short-lived community:

Public,

Audience

In large social groups, lifestyle, morals, customs, national characteristics, language, folklore, traditions, etc. are subject to study. – what is called the psychology of peoples, mass phenomena.

Mores, customs, traditions are specific regulators of social behavior that do not exist in small groups.

The psychology of peoples is the science of the soul of a people, which is no less real than the individual psyche.

Characteristics large social groups are served by group needs, interests, values, stereotypes, social attitudes, mentality , which is understood as an integral characteristic of a certain culture, which reflects the uniqueness of the vision and understanding of the world by its representatives, their typical responses to the picture of the world. Representatives of a certain culture acquire similar ways of perceiving the world, form a similar way of thinking, which is expressed in specific patterns of behavior (G.N. Andreeva). As well as some specific characteristics of individual groups, for example, a set of social roles (social classes and strata, gender groups), national character (ethnic group).

Psychology of a large organized group is something common that is inherent to one degree or another in all representatives of a given group, i.e. typical for them, generated general conditions existence. This typical is not the same for everyone, but it is common. In the psychological structure of this group, almost all researchers (G.G. Diligensky, A.I. Goryacheva, Yu.V. Bromley, etc.) distinguish two components:

- mental makeup as a more stable formation (social and national character, mores, customs, traditions, tastes);

- emotional sphere, as a more mobile formation (needs, interests, moods).

Crowd as a type of spontaneous groups, according to the definition of G. Le Bon (1841–1931), it is “a human totality with a mental community.” A man of the masses or a man of the crowd has the following qualities:

Loss of ability to observe

Depersonalization, which leads to the dominance of impulsive, instinctive reactions,

The predominance of feelings over the intellect, which leads to exposure to various influences,

In general, loss of intelligence, which leads to the abandonment of logic,

Loss of personal responsibility, which leads to a lack of control over passions.

Weight– a more stable formation than a crowd, with unclear boundaries, more organized. A sign of a mass is a union of people who are concerned about the same topic and who quite consciously gather for the sake of some kind of action: a demonstration, a rally.

Public – a spontaneous community of people united only by a psychic connection, since it is disunited and therefore slower to join in any action (for example, the reading public, the theater audience, as well as a meeting of people for spending time together– at the stadium, in the auditorium).

In more confined spaces, such as lecture halls, the audience is often referred to as audience.

The public always gathers for the sake of a common and specific goal, therefore it is more manageable, and to a greater extent complies with the norms accepted in the chosen type of organization of spectacles.

For the nature of the impact in spontaneous groups specifically:

Contagion (unconscious, involuntary exposure of an individual to certain mental states),

Suggestion (purposeful, unreasoned influence of one person on another or on a group),

Imitation (reproduction by an individual of traits and patterns of demonstrated behavior)

10.2.1. Mass communication – communication of large social groups

The development of social relations is accompanied by a deepening of communication relations and the ramification of connections between person and person, people with people, i.e. development of social communication processes in its mass forms.

Mass communication acts as “the process of disseminating information (knowledge, spiritual values, moral and legal norms, etc.) to numerically large, dispersed audiences.”

Mass communication is a type of communication, namely socially oriented type of communication;

The structure of information in the field of mass communication covers the “spectrum types psychological impact from awareness (informing) and training to persuasion and suggestion”;

Mass communication provides indirect nature of communication, proposed modern technology transmitting and receiving information;

Mass communication constitutes an organic connection social system, in which she performs the role of a policy instrument and relay of ideas.

Mass communication systems(according to Yu.P. Budantsev):

· Primitive community – mass actions of the carnival type, folk processions, rituals, folk theater;

· The era of the decay of the primitive community - theatrical performances, religious services, various meetings of formal and informal groups;

· The era of the formation of class society - libraries, exhibitions, museums, visual propaganda;

· Modern era – transformation of “natural” contacts into “technical” ones.

Functions of mass communication:

· Dissemination of knowledge about reality, informing;

· Social control and management;

· Integration of society and its self-regulation;

· Formation of public opinion;

· Social education;

· Dissemination of culture;

· Social activation of the individual;

· Social relaxation.

Levels of interaction in the “mass communications – personality” system.

The nature and direction of the influence of mass communication depend on the choice of one of the fundamental impact programs - manipulative or formative.

Based on the activity model developed in Russian psychology, consisting of two subsystems: extraverted personality activity (block 1) and introverted personality activity (block 2), in Fig. 10.2 and 10.3 present the levels of this interaction.

In relation to the social psyche, mass communication plays several significant roles:

· Firstly, a regulator of the dynamic processes of the social psyche;

· Secondly, an integrator of mass sentiment;

· Thirdly, a channel for the circulation of psycho-formative information.

All this makes the organs of mass communication a powerful means of influencing a specific person, and therefore social groups.

Social psyche

Social psyche – a functional dynamic system of society, which is formed in the process of communication between individuals, large and small social groups and solves the problems of organizing and managing the joint activities of formal and informal associations. Its integrity is determined by:

The property of the individual psyches that form this system is

Mechanisms and nature of interaction between people through which they communicate: mechanisms of imitation, suggestive (suggestion) and authoritarian (power) communication, conformism.

The social psyche is a kind of abstract construct.

The structural formations of the social psyche are:

· Patterns and mechanisms of direct communication;

· Group mental phenomena, states and processes (collective feelings, group opinions, crowd feeling, customs, traditions, norms) arising as a result of communication;

· Stable mental characteristics of various social groups (gender, age, demographic, national characteristics), expressed in social values and attitudes;

· Mental states of the individual in the group, regulation of the individual’s behavior in the group (role prescriptions, motives, etc.).

Functions of the social psyche:

· Integration (unification);

· Translation of social experience (society provides the individual with social experience and through this the system itself is reproduced);

· Social adaptation (the social psyche ensures a person’s entry into society);

· Social correlation (social psyche correlates the human psyche, i.e. brings human behavior into line with existing norms and values);

· Social activation (the social psyche is capable of strengthening and intensifying human activity with the help of group norms, goals, values, creating mass emotions as a stimulator of mass activity);

· Social control (the social psyche acts as a system of formal and informal regulators through institutions that inform, correct, broadcast and punish);

· Psychological relief (through sports events, shows, etc.)

Small social groups

In the structure of social psychology problems, the small group problem is the most traditional and well developed.

Under small group refers to a small group whose members are united by a common social activities and are in direct personal communication, which is the basis for the emergence of emotional relationships, group norms and group processes.

Classification of small groups

The most common are three classifications:

1. Division of small groups into “primary” and “secondary”;

2. Dividing them into “formal” and “informal”;

3. Division into “membership groups” and “reference groups”.

✓ Dividing small groups into primary And secondary was first proposed by C. Cooley, who simply gave a descriptive definition of the primary group, naming such as family, group of friends, group of closest neighbors. Later, Cooley identified an essential feature of the primary group - the immediacy of contacts, but when this feature was identified, the primary groups began to be identified with small groups, and then the classification lost its meaning. Traditionally, the division of groups into primary and secondary is preserved (secondary in this case are those where there are no direct contacts, and various intermediaries are used for communication between members in the form of, for example, means of communication), but in essence it is the primary groups that are studied, because only they satisfy the small group criterion.

✓ Dividing small groups into formal And informal was first proposed by E. Mayo during his famous Hawthorne experiments. According to Mayo, a formal group is distinguished by the fact that all the positions of its members are clearly defined in it; they are prescribed by group norms. Accordingly, in a formal group, the roles of all group members are also strictly distributed, in a system of subordination to the so-called power structure: the idea of vertical relationships as relationships defined by a system of roles and statuses. An example of a formal group is any group created in the context of a specific activity: a work team, a school class, a sports team, etc. Within formal groups, Mayo also discovered informal groups that develop and arise spontaneously, where neither statuses nor roles are prescribed, where there is no set system of vertical relationships. An informal group can be created within a formal one, when, for example, in a school class, groups arise consisting of close friends united by some common interest. An informal group can also arise on its own, not inside the formal group, but outside it: a group of tourists, people who accidentally united to play beach volleyball, a group of friends belonging to completely different formal groups, etc.

Informal small groups are associations of people that arise on the basis of the internal needs inherent in individuals themselves, primarily for communication, belonging, understanding, sympathy, love.

Due to the fact that in reality it is difficult to isolate strictly formal and strictly informal groups, the concepts of formal And informal structures groups (or the structure of formal and informal relations), and it was not the groups that began to differ, but the type, the nature of the relationships within them.

It should be noted that in the definition of a formal group, the word “formal” does not contain any negative connotations (in particular, it does not mean the formalism of relationships). More precisely, this formalized group.

✓ Dividing small groups into groups membership And referential group was introduced by the American psychologist G. Hyman, who discovered the very phenomenon of the “reference group”. Such groups, in which a person is not really included, but whose norms he accepts, are called reference groups by Hyman.

In the works of M. Sherif, the concept of a reference group was associated with a “frame of reference” that an individual uses to compare his status with the status of other persons. G. Kelly, developing the concepts of reference groups, identified two of their functions: comparative and normative: an individual needs a reference group either as a standard for comparing his behavior with it, or for normative assessment of it.

Currently, as noted by social psychologist G.M. Andreeva, there is a dual use of the term “reference group”: sometimes as a group opposing the membership group, sometimes as a group arising within the membership group. In the second case, the reference group is defined as "significant social circle", i.e. as a circle of persons selected from a real group as especially significant for the individual.

There is also a more expanded interpretation of the reference group, in which it can include people who are not actually included in the same group. For example, for a teenager, the reference group can be a father, a friend, an idol, a literary hero, etc.

If a membership group has lost its attractiveness for an individual, then he begins to compare his behavior with another group - a reference (meaningful) one for him.

Group dynamics

The term “group dynamics” was first used by K. Levin (1939). According to his definition, “group dynamics” is a discipline that studies the positive and negative forces that operate in a given group. When describing and explaining the principles of group dynamics, K. Lewin relied on the laws of Gestalt psychology.

If we consider the group as a whole, then some patterns of group dynamics can be explained by the action of two basic laws of Gestalt psychology:

1. The whole dominates its parts.

A group is not just a sum of individuals: it modifies the behavior of its members;

From the outside it is easier to influence the behavior of an entire group than the behavior of an individual member;

Each member acknowledges that he is dependent on all other members.

2. Individual elements are combined into a whole.

It is not similarity, but the interrelationship of members that is the basis for the formation of a group;

A person tends to become a member of the group with which he identifies himself, and not at all of the one on which he most depends;

A person remains among those to whom he feels he belongs, even if their behavior seems unfair and the pressure unfriendly.

In the modern understanding, group dynamics is the development or movement of a group over time, determined by the interaction and relationships of group members with each other, as well as external influences on the group.

The concept of group dynamics includes five main and several additional elements.

Essential elements:

Group norms

Group structure,

Group cohesion,

Phases of group development.

Additional items:

Creation of a subgroup (as the development of the group structure),

The relationship of the individual with the group (also considered as the development of the group structure).

Let's consider basic elements of group dynamics.

✓Group goals are determined by what more common system practical work the group is included with people, and to a large extent - personal qualities its leader. The goals of the group may not coincide with the goals of its individual members. This gives rise to group dynamics, the results of which are not always predictable.

✓ Group norms arise as a result of the pursuit of a common goal, the desire to maintain the stability of the group, common ideas that have developed in the group, imitation of other groups, fear of sanctions.

All group norms are social norms, i.e. represent “establishments, models, standards of behavior, from the point of view of society as a whole and social groups and their members.” In a narrower sense, group norms are certain rules that are developed by a group, accepted by it, and to which the behavior of its members must obey in order for their stay in the group to be possible. Norms perform a regulatory function in relation to each of its members. Group norms are associated with values , since any rules can be formulated only on the basis of the acceptance or rejection of some socially significant phenomena.

It is possible to understand the relationship of an individual with a group only by identifying which group norms he accepts and which he rejects, what values he shares and why he does so. All this takes on special significance when there is a mismatch between the norms and values of the group and society, when the group begins to focus on values that do not coincide with the norms of society. Important problem- This measure acceptance of norms by each group member: how social, group and personal norms relate to him.

Mechanisms by which a group “brings” its member back onto the path of norm compliance are: sanctions . Sanctions can be of two types: incentives And prohibitive.

The relationship between an individual’s status in a group and compliance with norms has been revealed: as a rule, people with high status are more conforming and strive to conform to norms to a greater extent; they are sometimes more “allowed” to break norms.

✓ Group structure, First of all, it includes two elements of life:

Composition (composition) of the group - age, professional or social characteristics of the group;

Varieties of its structures are the structure of interpersonal relationships between group members, the structure of power, the structure of communications, etc.

The structure of interpersonal relationships involves, first of all, clarifying the position of the individual in the group as its member. The following concepts are used here:

- “status” or “position” – the place of the individual in the system of group life;

- “role” is a dynamic aspect of status, which is revealed through a list of those real functions performed by an individual in a group in accordance with the content of group activity;

The system of “group expectations” - this term refers to the fact that each member of the group not only performs his functions in it, but is also necessarily perceived and evaluated by others: from each position, from each role, it is expected not only to perform certain functions, but also quality their implementation.

In a number of cases, a discrepancy may arise between the expectations that the group has regarding any of its members and his actual behavior, the actual way he fulfills his role. In order for this system of expectations to be somehow defined, there are group norms And group sanctions(see above).

Power structure does not mean forms of political power, but a purely psychological distribution of relations of management/leadership and subordination. Studies have identified various shapes authorities: awarding(existing, for example, to maintain consent); coercive(necessary, for example, to maintain discipline); expert(based on special knowledge that may be in demand in some special situations); informational(based on belief).

Communication structure shows how clearly and well the necessary information is distributed in the group, and how it is exchanged between group members.

There are several communication network models (Fig. 10.4):

A – “ring”. In a ring network, each communication participant interacts with only two other participants. Information moves in a circle, the process of its dissemination is not coordinated by anyone. All participants have equal powers.

B – “Igrek”. The graphical representation of this type of network resembles the Latin letter Y. Each participant in the communication process interacts with one, two or three other participants, depending on their position in the network structure. Those of them who find themselves at the extreme points of the network - at the base of the letter Y and at the two upper ends - can enter into the communication process with only one partner. The person occupying the middle position can interact with three partners - this person is the most significant figure in the network, the remaining participants can only interact with two others.

B – “star”. The person who occupies a central place in the structure of this network interacts with all participants in the communication process, while they are not interconnected. All information is transmitted to the center and comes from there. This type of communication network is used in many companies, when the head of the company coordinates the activities of department heads.

G – “wheel”. This type of network is similar to a “ring”, since all its participants have equal rights, but differs in that each participant interacts not with two, but with three other network participants.

Leavitt found that the greatest accuracy in the transfer of information is achieved in the Igrek network. In a ring network, failures in information transmission occur more often, apparently because in this case no one coordinates the communication process. However, members of a ring network, like members of a wheel-type network, are more likely to be satisfied with their interactions with each other. If we rank the degree of satisfaction of participants in different types of network communication, we can say that the person at the center of the “star” receives the greatest satisfaction. He is followed by a person who occupies a central position in the “Y” network. The least satisfied participants are those located on the rays of the “star”. Based on these observations, Leavitt concluded that the key factor in satisfaction is the degree of human participation in the common cause. People like it when something depends on them.

✓ Group cohesion or group cohesion is a process/indicator of the formation/formation of a special type of connections in a group that allows an externally given structure to be transformed into a psychological community of people, into a complex psychological organism living according to its own laws.

Sociometry proposed a special “group cohesion index,” which was calculated as the ratio of the number of mutual positive choices to the total number of possible choices. The “group cohesion index” is a strictly emotional characteristic of a small group.

S. Kratochvil highlights the following factors cohesion:

Satisfying the personal needs of individuals in or through a group;

Group goals that are consistent with individual needs; mutual dependence when working on specific tasks;

The benefits arising from group membership and the expectation of undoubted benefits from it;

Various kinds of sympathies between group members, their mutual attraction;

Each member's motivation for membership in the group, including the efforts he made to get into it;

Friendly, inviting atmosphere;

The prestige of the group, and therefore of membership in it;

Impact of group activities:

Attractiveness general actions(interesting, fun, exciting activities that evoke a general experience of positive emotions),

Group techniques for enhancing group cohesion

Rivalry with another group or groups;

Hostile, hostile attitude of society towards a group.

As a result of the grouping of people with different positions, views, behavior patterns, plans and needs, tension arises in relationships.

It is clear that there is a need to ensure a dynamic balance between cohesion and tension (cohesive people feel supported by each other, and tension in relationships creates dissatisfaction with themselves and other group members).

Mechanisms of group dynamics. Researchers of group dynamics problems identify three of its mechanisms:

resolution of intragroup contradictions;

“idiosyncratic credit”;

psychological exchange.

Expression intragroup contradictions turns out to be a conflict. In the theory of group dynamics, he acts as an integrator of new structures. M.-A. Robber and F. Thälmann, classifying the sources of conflicts, identify:

- personal conflict(when the tension that arises in one of the group members causes tension in the group and ends with its restructuring);

- interpersonal conflict(between two or more group members);

- belonging conflict(as a result of dual membership in different groups, and also as a result of a decrease in the prestige of the group);

- intergroup conflict(arising due to the divergence of interests of two or more groups);

- social conflict(as a result of tension in society).

As a result of resolving the conflict in the group, organizational changes (goals, action plans, group structure), change of leader, removal of dissidents, formation of subgroups, etc. may occur.

Term "idiosyncratic credit" introduced by E. Hollander, denotes the behavior of those deviating from group norms. This means that “idiosyncratic credit” is a mechanism of group dynamics when a group gives permission for deviant behavior to its leader or individual members in the name of achieving set goals. Deviance of behavior has the nature of innovation and triggers a new mechanism of group dynamics.

Psychological exchange many authors define it through value exchange. So R.L. Krichevsky and E.M. Dubovskaya value exchange refers to the mutual satisfaction of the participants in the interaction of certain social needs through the mutual provision of corresponding values.

Small group development

Phases of group development. According to strategic concept A.V. Perovsky, the phases of group development are determined by the following criteria:

Firstly, the degree of mediation of interpersonal relationships in the group by the content of joint activities;

Secondly, the social significance of joint activities.

Based on these criteria, A.V. Petrovsky identifies the following phases of development of a small group:

diffuse group– a community in which interpersonal relationships are not mediated by the content of joint activity, its goals, significance and values;

association group– belonging to a community begins to be recognized as a condition for the effectiveness of further actions;

group-cooperation– interpersonal relationships are mediated by the content of joint activity that is meaningful to everyone;

team group– interpersonal relationships are mediated by the personally significant and socially valuable content of group activity;

corporation- a group in which interpersonal relationships are mediated by the content of group activity that is personally significant for its members, but also social, and sometimes antisocial in its attitudes.

A parametric approach to the dynamics of group development, proposed by L.I. Umansky, defines the following scheme:

At the center of the continuum is conglomerate group, i.e. a group consisting of people unfamiliar with each other, and at the poles - "team" And "anti-collective".

The development of a group towards the pole of the “collective” is associated with the group passing through two qualitative stages – cooperation and autonomization. At the same time, such stages of development as “nominal group” and “association group” are also possible between a cooperation group and a conglomerate group.

The two-factor model of B. Tuckman is also known. He describes the dynamics of group development based on the conditions in which it is formed, highlighting two spheres of group activity: business (solving a group problem) and interpersonal (developing a group structure). It is assumed that in each of these areas the group goes through four stages of its development (Fig. 10.5).

I. Yalom and K. Heck identify the following phases of group development:

Phase I – orientation and dependence, uncertainty, adaptation, passive tension;

Phase II – development of cohesion and cooperation, structuring the group in the fight against external interference, constructiveness, active work;

Phase III – phase of purposeful activity.

Introduction

The concept of "social group"

Classification of social groups:

a) division of groups based on the individual’s membership in them;

b) groups divided by the nature of the relationships between their members:

1) primary and secondary groups;

2) small and large groups

4. Conclusion

5. List of used literature

Introduction

Society is not just a collection of individuals. Among large social communities there are classes, social strata, estates. Each person belongs to one of these social groups or may occupy some kind of intermediate (transitional) position: having broken away from the usual social environment, he has not yet fully integrated into the new group; in his way of life, the features of the old and new social status are preserved.

The science that studies the formation of social groups, their place and role in society, and the interaction between them is called sociology. There are different sociological theories. Each of them gives its own explanation of the phenomena and processes occurring in social sphere life of society.

In my essay, I would like to cover in more detail the question of what a social group is, and consider the classification of social groups.

The concept of "social group"

Despite the fact that the concept of group is one of the most important in sociology, scientists do not fully agree on its definition. First, the difficulty arises from the fact that most concepts in sociology appear in the course of social practice: they begin to be used in science after a long time of their use in life, and at the same time they are given very different meanings. Secondly, the difficulty is due to the fact that many types of communities are formed, as a result of which, in order to accurately determine a social group, it is necessary to distinguish certain types from these communities.

There are several types of social communities to which the concept of “group” is applied in the ordinary sense, but in the scientific sense they represent something different. In one case, the term “group” refers to some individuals physically, spatially located in a certain place. In this case, the division of communities is carried out only spatially, using physically defined boundaries. An example of such communities could be individuals traveling in the same carriage, located at a certain moment on the same street, or living in the same city. In a strictly scientific sense, such a territorial community cannot be called a social group. It is defined as aggregation- a certain number of people gathered in a certain physical space and not carrying out conscious interactions.

The second case is the application of the concept of group to a social community that unites individuals with one or more similar characteristics. Thus, men, school graduates, physicists, old people, smokers appear to us as a group. Very often you can hear the words about “the age group of young people from 18 to 22 years old.” This understanding is also not scientific. To define a community of people with one or more similar characteristics, the term “category” is more accurate. For example, it is quite correct to talk about the category of blondes or brunettes, the age category of young people from 18 to 22 years old, etc.

Then what is a social group?

A social group is a collection of individuals interacting in a particular way based on the shared expectations of each group member regarding the others.

In this definition one can see two essential conditions necessary for a group to be considered a group:

1) the presence of interactions between its members;

2) the emergence of shared expectations of each group member regarding its other members.

By this definition, two people waiting for a bus at a bus stop would not be a group, but could become one if they engaged in a conversation, fight, or other interaction with mutual expectations. Airplane passengers cannot be a group. They will be considered an aggregation until groups of people interacting with each other are formed among them during travel. It happens that an entire aggregation can become a group. Suppose a certain number of people are in a store where they form a queue without interacting with each other. The seller leaves unexpectedly and is absent for a long time. The queue begins to interact to achieve one goal - to return the seller not him workplace. An aggregation becomes a group.

At the same time, the groups listed above appear unintentionally, by chance, they lack stable expectations, and interactions, as a rule, are one-sided (for example, only conversation and no other types of interactions). Such spontaneous, unstable groups are called quasigroups. They can develop into social groups if, through ongoing interaction, the degree of social control between its members increases. To achieve this control, some degree of cooperation and solidarity is necessary. Indeed, social control in a group cannot be exercised as long as individuals act randomly and separately. It is impossible to effectively control a disorderly crowd or the actions of people leaving the stadium after the end of a match, but it is possible to clearly control the activities of the enterprise team. It is precisely this control over the activities of the team that defines it as a social group, since the activities of people in this case are coordinated. Solidarity is necessary for a developing group to identify each group member with the collective. Only if group members can say “we”, stable group membership and boundaries of social control are formed (Fig. 1).

From Fig. 1 shows that in social categories and social aggregations there is no social control, so these are purely abstract identifications of communities based on one characteristic. Of course, among individuals included in a category, one can notice a certain identification with other members of the category (for example, by age), but, I repeat, there is practically no social control here. A very low level of control is observed in communities formed according to the principle of spatial proximity. Social control here comes simply from the awareness of the presence of other individuals. Then it intensifies as quasi-groups transform into social groups.

Social groups themselves also have varying degrees of social control. Thus, among all social groups, a special place is occupied by the so-called status groups - classes, strata and castes. These large groups, which arose on the basis of social inequality, have (with the exception of castes) low internal social control, which, nevertheless, can increase as individuals become aware of their belonging to a status group, as well as awareness of group interests and inclusion in the struggle to improve their status. groups. In Fig. 1 shows that as the group gets smaller, social control increases and the strength of social connections increases. This is because as group size decreases, the number of interpersonal interactions increases.

Classification of social groups

Dividing groups based on characteristics

individual's belonging to them

Each individual identifies a certain set of groups to which he belongs and defines them as “mine”. This could be “my family”, “my professional group”, “my company”, “my class”. Such groups will be considered ingroups, i.e. those to which he feels that he belongs and in which he identifies with other members in such a way that he regards the group members as “we”. Other groups to which the individual does not belong - other families, other groups of friends, other professional groups, other religious groups - will be for him outgroups, for which he selects symbolic meanings: “not us”, “others”.

In the least developed, primitive societies, people live in small groups, isolated from each other and representing clans of relatives. Kinship relations in most cases determine the nature of ingroups and outgroups in these societies. When two strangers meet, the first thing they do is look for family ties, and if any relative connects them, then both of them are members of the ingroup. If family ties are not found, then in many societies of this type people feel hostile towards each other and act in accordance with their feelings.

IN modern society relationships between its members are built on many types of connections in addition to family ones, but the feeling of an ingroup and the search for its members among other people remain very important for every person. When an individual finds himself among strangers, he first of all tries to find out whether among them there are those who make up his social class or layer and adhere to his political views and interests. For example, someone who plays sports is interested in people who understand sports events, and even better, who support the same team as him. Avid philatelists involuntarily divide all people into those who simply collect stamps and those who are interested in them, and look for like-minded people by communicating in different groups. Obviously, a sign of people belonging to an ingroup should be that they share certain feelings and opinions, say, laugh at the same things, and have some unanimity regarding areas of activity and goals in life. Members of an outgroup may have many traits and characteristics common to all groups of a given society, may share many feelings and aspirations common to all, but they always have certain private traits and characteristics, as well as feelings that are different from the feelings of members of the ingroup. And people unconsciously note these traits, dividing previously unfamiliar people into “us” and “others.”

In modern society, an individual belongs to many groups at the same time, so a large number of in-group and out-group connections can overlap. An older student will view a junior student as an individual belonging to an outgroup, but a junior student and a senior student may be members of the same sports team, where they are part of the ingroup.

Researchers note that in-group identifications, intersecting in many directions, do not reduce the intensity of self-determination of differences, and the difficulty of including an individual in a group makes exclusion from in-groups more painful. Thus, a person who unexpectedly received a high status has all the attributes to get into high society, but cannot do this, since he is considered an upstart; a teenager desperately hopes to join a youth team, but she doesn't accept him; a worker who comes to work in a brigade cannot fit in and is sometimes the subject of ridicule. Thus, exclusion from groups can be a very cruel process. For example, most primitive societies consider strangers to be part of the animal world; many of them do not distinguish between the words “enemy” and “stranger,” considering these concepts to be identical. The attitude of the Nazis, who excluded Jews from human society, is not too different from this point of view. Rudolf Hoss, who led the concentration camp at Auschwitz, where 700 thousand Jews were exterminated, characterized this massacre as “the removal of alien racial-biological bodies.” In this case, in-group and out-group identifications led to fantastic cruelty and cynicism.

To summarize what has been said, it should be noted that the concepts of ingroup and outgroup are important because the self-attribution of each individual to them has a significant impact on the behavior of individuals in groups; everyone has the right to expect recognition, loyalty, and mutual assistance from members - associates in the ingroup. The behavior expected from outgroup representatives when meeting depends on the type of outgroup. From some we expect hostility, from others - more or less friendly attitude, from others - indifference. Expectations of certain behavior from outgroup members undergo significant changes over time. Thus, a twelve-year-old boy avoids and does not like girls, but a few years later he becomes a romantic lover, and a few years later a spouse. During a sports match, representatives of different groups treat each other with hostility and may even hit each other, but as soon as the final whistle sounds, their relations change dramatically, becoming calm or even friendly.

We are not equally included in our ingroups. Someone may, for example, be the life of a friendly company, but not be respected in the team at their place of work and be poorly included in intra-group connections. There is no equal assessment by the individual of the outgroups surrounding him. A zealous follower of religious teaching will be closed to contacts with representatives of the communist worldview more than with representatives of social democracy. Everyone has their own scale for assessing outgroups.

R. Park and E. Burgess (1924), as well as E. Bogardus (1933), developed the concept of social distance, which allows one to measure the feelings and attitudes expressed by an individual or social group towards various outgroups. Ultimately, the Bogardus Scale was developed as a measure of the degree of acceptance or closedness towards other outgroups. Social distance is measured by looking separately at the relationships people have with members of other outgroups. There are special questionnaires, by answering which members of one group assess relationships, rejecting or, conversely, accepting representatives of other groups. Informed group members are asked, when filling out questionnaires, to note which of the members of other groups they know they perceive as a neighbor, a workmate, or a marriage partner, and thus relationships are determined. Questionnaires measuring social distance cannot accurately predict what people will do if a member of another group actually becomes a neighbor or workmate. The Bogardus scale is only an attempt to measure the feelings of each member of the group, the disinclination to communicate with other members of this group or other groups. What a person will do in any situation depends to a great extent on the totality of conditions or circumstances of that situation.

Reference groups

The term “reference group”, first coined by social psychologist Mustafa Sherif in 1948, means a real or conditional social community with which an individual relates himself as a standard and to whose norms, opinions, values and assessments he is guided in his behavior and self-esteem. A boy, playing the guitar or playing sports, is guided by the lifestyle and behavior of rock stars or sports idols. An employee of an organization, striving to make a career, is guided by the behavior of top management. It may also be noted that ambitious people who suddenly receive a lot of money tend to imitate the representatives of the upper classes in dress and manners.

Sometimes the reference group and the ingroup may coincide, for example, in the case when a teenager focuses on his company to a greater extent than on the opinion of teachers. At the same time, an outgroup can also be a reference group; the examples given above demonstrate this.

There are normative and comparative referent functions of the group.

The normative function of the reference group is manifested in the fact that this group is the source of norms of behavior, social attitudes and value orientations of the individual. Thus, a little boy, wanting to quickly become an adult, tries to follow the norms and value orientations accepted among adults, and an emigrant coming to a foreign country tries to master the norms and attitudes of the natives as quickly as possible, so as not to be a “black sheep.”

The comparative function is manifested in the fact that the reference group acts as a standard by which an individual can evaluate himself and others. If a child perceives the reaction of loved ones and believes their assessments, then a more mature person selects individual reference groups, belonging or not belonging to which is especially desirable for him, and forms a self-image based on the assessments of these groups.

Stereotypes