Underwater plane. Soviet flying submarine It turned out that the United States brought to life the idea of a flying submarine

Flying submarine - aircraft, which combined the ability of a seaplane to take off and land on water and the ability of a submarine to move underwater.

If you have ever watched or are going to watch the movie "The First Avenger", then you will be able to see just such a plane-submarine at the beginning of the film.

In the USSR, on the eve of the Second World War, a project for a flying submarine was proposed - a project that was never realized. From 1934 to 1938 The flying submarine project (abbreviated: LPL) was led by Boris Ushakov. The LPL was a three-engine, two-float seaplane equipped with a periscope. Even while studying at the Higher Marine Engineering Institute named after F. E. Dzerzhinsky in Leningrad (now the Naval Engineering Institute), from 1934 until his graduation in 1937, student Boris Ushakov worked on a project in which the capabilities of a seaplane were supplemented capabilities of the submarine. The invention was based on a seaplane capable of diving under water.

In 1934, a cadet at VMIU named after. Dzerzhinsky B.P. Ushakov presented a schematic design of a flying submarine (LPL), which was subsequently redesigned and presented in several versions to determine the stability and loads on the structural elements of the device.

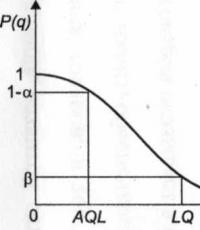

In April 1936, a review by Captain 1st Rank Surin indicated that Ushakov’s idea was interesting and deserved unconditional implementation. A few months later, in July, the semi-draft design of the LPL was considered by the Scientific Research Military Committee (NIVK) and received a generally positive review, containing three additional points, one of which read: “... It is advisable to continue the development of the project in order to identify the reality of its implementation by carrying out the corresponding calculations and the necessary laboratory tests...” Among those who signed the document were the head of the NIVK, military engineer 1st rank Grigaitis, and the head of the department of combat tactics, flagship 2nd rank Professor Goncharov.

In 1937, the topic was included in the plan of department “B” of the NIVK, but after its revision, which was very typical for that time, it was abandoned. All further development was carried out by the engineer of department “B”, military technician 1st rank B.P. Ushakov, during off-duty hours.

On January 10, 1938, in the 2nd department of the NIVK, a review of sketches and main tactical and technical elements LPL prepared by the author. What was the project? The flying submarine was intended to destroy enemy ships on the open sea and in the waters of naval bases protected by minefields and booms. The low underwater speed and limited cruising range underwater of the LPL were not an obstacle, since in the absence of targets in a given square (area of operation), the boat could find the enemy on its own. Having determined its course from the air, it sat below the horizon, which excluded the possibility of its premature detection, and sank along the ship’s path. Until the target appeared at the salvo point, the LPL remained at depth in a stabilized position, without wasting energy by unnecessary moves.

If the enemy deviated within an acceptable range from the course line, the LPL approached him, and if the target deviated too much, the boat let it go beyond the horizon, then surfaced, took off, and prepared to attack again.

A possible repeat approach to a target was considered one of the significant advantages of an underwater torpedo bomber over traditional submarines. The action of flying submarines in a group should have been especially effective, since theoretically three such devices would create an impenetrable barrier up to nine miles wide in the enemy’s path. The LPL could penetrate enemy harbors and ports at night, dive, and during the day conduct surveillance, find direction of secret fairways, and attack when the opportunity presented itself. The design of the LPL provided for six autonomous compartments, three of which housed AM-34 aircraft engines with a power of 1000 hp each. every. They were equipped with superchargers that allowed boosting up to 1200 hp during takeoff. The fourth compartment was residential, designed for a team of three people. From it the ship was controlled under water. The fifth compartment contained a battery, and the sixth compartment contained a 10 hp electric propulsion motor. The durable body of the LPL was a cylindrical riveted structure with a diameter of 1.4 m made of 6 mm thick duralumin. In addition to durable compartments, the boat had a lightweight wet-type pilot's cabin, which was filled with water when submerged, while the flight instruments were sealed in a special shaft.

The skin of the wings and tail was supposed to be made of steel, and the floats of duralumin. These structural elements were not designed for increased external pressure, since during immersion they were flooded with sea water that flowed by gravity through scuppers (holes for water drainage). Fuel (gasoline) and oil were stored in special rubber tanks located in the center section. During the dive, the inlet and outlet lines of the water cooling system of the aircraft engines were blocked, which prevented their damage under the influence of seawater pressure. To protect the hull from corrosion, the hull was painted and varnished. Torpedoes were placed under the wing consoles on special holders. The boat's design payload was 44.5% of the vehicle's total flight weight, which was typical for heavy-duty vehicles.

The diving process included four stages: battening down the engine compartments, shutting off the water in the radiators, transferring the controls to underwater, and moving the crew from the cockpit to the living compartment (central control station).”

The submerged motors were covered with metal shields. The LPL was supposed to have 6 sealed compartments in the fuselage and wings. Mikulin AM-34 motors of 1000 hp each were installed in three compartments that were sealed during immersion. With. each (with a turbocharger in takeoff mode up to 1200 hp); the sealed cabin had to contain instruments, a battery and an electric motor. The remaining compartments should be used as tanks filled with ballast water for immersing LPLs. Preparing for the dive should only take a couple of minutes.

The fuselage was supposed to be an all-metal duralumin cylinder with a diameter of 1.4 m and a wall thickness of 6 mm. The pilot's cabin filled with water during the dive. Therefore, all devices were supposed to be installed in a waterproof compartment. The crew had to move to the diving control compartment, located further in the fuselage. The supporting planes and flaps must be made of steel, and the floats must be made of duralumin. These elements were supposed to be filled with water through the valves provided for this in order to equalize the pressure on the wings during diving. Flexible fuel tanks and lubricants must be located in the fuselage. For corrosion protection, the entire aircraft had to be covered with special varnishes and paints. Two 18-inch torpedoes were suspended under the fuselage. The planned combat load was supposed to be 44.5% of the total weight of the aircraft. This is a typical value for heavy aircraft of that time. To fill the tanks with water, the same electric motor was used to ensure movement under water.

In 1938, the research military committee of the Red Army decided to curtail work on the Flying Submarine project due to the insufficient mobility of the submarine underwater. The decree stated that after the LPL was discovered by the ship, the latter would undoubtedly change course. This will reduce the combat value of the LPL and will most likely lead to mission failure.

It should be noted that this was not the only domestic project of a flying submarine. At the same time, in the thirties of the last century, I.V. Chetverikov presented a project for a two-seater flying submarine SPL-1 - “an aircraft for submarines.” To be more precise, it was a seaplane that was stored disassembled on a submarine, and upon surfacing it could be easily assembled. This project was a kind of flying boat, the wings of which folded along the sides. Power point leaned back, and the floats located under the wings were pressed against the fuselage. The tail “empennage” was also partially folded. The dimensions of the SPL-1 when folded were minimal - 7.5 x 2.1 x 2.4 m. Disassembling the aircraft took only 3 - 4 minutes, and preparing it for flight took no more than five minutes. The aircraft storage container was a pipe with a diameter of 2.5 and a length of 7.5 meters.

It is noteworthy that the building materials for such a boat-plane were wood and plywood with fabric covering of the wing and “tail”, while the weight empty plane managed to reduce to 590 kg. Despite this seemingly unreliable design, during testing pilot A.V. Krzhizhevsky managed to reach a speed of 186 km/h on the SPL-1. And two years later, on September 21, 1937, he set three international records in the light seaplane class with this machine: speed at a distance of 100 km - 170.2 km/h, range - 480 km and flight altitude - 5,400 m.

In 1936, the SPL-1 aircraft was successfully demonstrated at the International Aviation Exhibition in Milan.

And this project, unfortunately, never entered mass production.

German project

In 1939, large submarines were planned for construction in Germany, and it was then that the project of the so-called “Eyes of the Submarine” was presented, a small float plane that could be assembled and folded into the shortest possible time and placed in a limited space. At the beginning of 1940, the Germans began producing six prototypes under the designation Ar.231.

The devices were equipped with 6-cylinder air-cooled Hirt NM 501 engines and had a lightweight metal structure. To facilitate folding of the wings, a small section of the center section was mounted above the fuselage on struts at an angle so that the right console was lower than the left, allowing the wings to be folded one above the other when turning around the rear spar. The two floats were easily detached. When disassembled, the aircraft fit into a pipe with a diameter of 2 meters. It was assumed that the Ar.231 was to be lowered and raised aboard the submarine using a folding crane. The process of disassembling the aircraft and storing it in the tubular hangar took six minutes. Assembly took about the same amount of time. For a four-hour flight, a significant supply of fuel was placed on board, which expanded the possibilities when searching for a target.

The first two Ar.231 devices V1 and V2 saw the sky at the beginning of 1941, but they were not successful. The flight characteristics and behavior of the small aircraft on the water turned out to be inadequate. In addition, the Ar.231 could not take off at wind speeds of more than 20 knots. In addition, the prospect of being on the surface for 10 minutes while assembling and disassembling the aircraft did not sit well with submarine commanders. In the meantime, the idea arose to provide aerial reconnaissance using the Focke-Angelis Fa-330 gyroplane, and although all six Ar.231s were completed, the aircraft did not receive further development.

"Fa-330" was the simplest design with a three-blade propeller without a mechanical engine. Before the flight, the propeller was untwisted using a special cable, and then the gyroplane was towed by a boat on a 150-meter-long leash.

Essentially, the Fa-330 was a large kite that flew at the expense of the speed of the submarine itself. Through the same cable was carried out telephone communications with the pilot. With a flight altitude of 120 meters, the viewing radius was 40 kilometers, five times greater than from the boat itself.

The disadvantage of the design was the long and dangerous procedure for landing the gyroplane on the deck of the boat. If she needed an urgent dive, she had to abandon the pilot along with his helpless unit. As a last resort, the reconnaissance officer relied on a parachute.

Already at the end of the war, in 1944, the Fa-330, which was not very popular among German submariners, was upgraded to the Fa-336, adding a 60-horsepower engine and turning it into a full-fledged helicopter. This innovation, however, did not have much impact on Germany’s military successes.

American RFS-1 or LPL Reida

The RFS-1 was designed by Donald Reid using parts from planes that had crashed. A serious attempt to make an aircraft capable of serving as a submarine, Reid's project came to him almost by accident when a set of model airplane wings fell off the skin and landed on the fuselage of one of his radio-controlled submarines, which he had been developing since 1954. Then the idea was born to build the world's first flying submarine.

First, Reid tested models of different sizes of flying submarines, then tried to build a manned vehicle. As an aircraft it was registered N1740 and was equipped with a 4-cylinder 65 hp engine. In 1965, the RFS-1 made its first flight, piloted by Don's son, Bruce, and flew over 23 m. The pilot's seat was initially in the engine pylon, then moved to the fuselage before the first flight.

In order to convert an airplane into a submarine, the pilot had to remove the propeller and cover the engine with a rubber “diving bell.” At auxiliary power, small 1 hp. the electric motor was located in the tail, the boat moved underwater, the pilot used scuba gear at a depth of 3.5 m.

Underpowered, Reid's RFS-1, also known as the Flying Submarine, actually flew, briefly, but it still managed to maintain flight and was capable of submersion. Don Reid tried to interest the military in this device, but to no avail. He died at the age of 79 in 1991.

Japan has gone the furthest

Japan also could not ignore such an exciting idea. There, airplanes became almost the main weapon of submarines. The vehicle itself turned from a reconnaissance aircraft into a full-fledged attack aircraft.

The appearance of such an aircraft for a submarine as the Seyran (Mountain Fog) turned out to be an extraordinary event. It was actually an element of a strategic weapon that included a bomber aircraft and a submersible aircraft carrier. The aircraft was designed to bomb targets in the United States of America that no conventional bomber could reach. The main bet was made on complete surprise.

The idea of a submarine aircraft carrier was born in the minds of the Imperial Japanese Naval Headquarters a few months after the outbreak of the Pacific War. It was intended to build submarines that were superior to anything previously created specifically for transporting and launching attack aircraft. A flotilla of such submarines would cross the Pacific Ocean, launch their aircraft directly in front of the chosen target, and then dive. After the attack, the planes had to go out to meet the underwater aircraft carriers, and then, depending on the weather conditions, the method of rescuing the crews was chosen. After this, the flotilla plunged under water again. For a greater psychological effect, which was placed above physical damage, the method of delivering the aircraft to the target should not have been disclosed.

Next, the submarines had to either go out to meet the supply ships to receive new aircraft, bombs and fuel, or act in the usual way using torpedo weapons.

The program, naturally, developed in an atmosphere of heightened secrecy and it is not surprising that the Allies first heard about it only after the surrender of Japan. At the beginning of 1942, the Japanese High Command issued an order to shipbuilders for the largest submarines built by anyone until the beginning of the atomic age in shipbuilding. It was planned to build 18 submarines. During the design process, the displacement of such a submarine increased from 4125 to 4738 tons, and the number of aircraft on board from three to four.

Now it was up to the plane. The fleet headquarters discussed the issue with the Aichi concern, which, starting in the 20s, built aircraft exclusively for the fleet. The Navy believed that the success of the whole idea depended entirely on the high performance of the aircraft. The plane had to combine high speed to avoid interception, with a long flight range (1500 km). But since the aircraft was intended for virtually one-time use, the type of landing gear was not even specified. The diameter of the underwater aircraft carrier's hangar was set at 3.5 m, but the fleet required that the aircraft fit in it without disassembly - the planes could only be folded.

Aichi designers, led by Tokuichiro Goake, considered this high requirements challenges to their talent and accepted them without objection. As a result, on May 15, 1942, the 17-C requirements for an experimental bomber for special missions appeared. The chief designer of the aircraft was Norio Ozaki.

The development of the aircraft, which received the corporate designation AM-24 and the short M6A1, proceeded surprisingly smoothly. The aircraft was created for the Atsuta engine, a licensed version of the 12-cylinder liquid-cooled Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine. From the very beginning, the use of detachable floats was envisaged for the only dismantled part of Seiran. Since the floats significantly reduced the aircraft's flight performance, provisions were made for releasing them in the air if such a need arose. In the submarine hangar, mounts for two floats were accordingly provided.

In the summer of 1942, a wooden model was ready, on which the folding of the wings and tail of the aircraft was mainly practiced. The wings were hydraulically rotated with the leading edge down and folded back along the fuselage. The stabilizer was manually folded down and the fin to the right. To operate at night, all folding units were coated with a luminous compound. As a result, the overall width of the aircraft was reduced to 2.46 m, and the height on the ejection trolley to 2.1 m. Since the oil in the aircraft systems could be heated while the submarine was under water, the aircraft could ideally be launched without landing gear from the catapult already 4.5 minutes after ascent. It took 2.5 minutes to attach the floats. All preparations for takeoff could only be carried out by four people.

The aircraft's structure was all-metal, with the exception of plywood covering the wing tips and fabric covering of the control surfaces. Double-slotted all-metal flaps could be used as air brakes. The crew of two people was located under a single canopy. In January 1943, it was decided to install a 13 mm Type 2 machine gun in the rear of the cabin. Offensive armament consisted of an 850 kg torpedo or one 800 kg or two 250 kg bombs.

At the beginning of 1943, six M6A1s were laid down at the Aichi plant in Nagoya, two of which were made in the training version M6A1-K on a wheeled chassis (the aircraft was called Nanzan (South Mountain)). The aircraft, with the exception of the fin tip, was almost no different from the main version, and even retained the attachment points to the catapult.

At the same time, in January 1943, the keel of the first submarine aircraft carrier I-400 was laid. Soon two more submarines I-401 and I-402 were laid down. Production of two more I-404 and I-405 was being prepared. At the same time, it was decided to build ten submarine aircraft carriers smaller than two Seirans. Their displacement was 3300 tons. The first of them, I-13, was laid down in February 1943 (according to the original plan, these boats were supposed to have only one reconnaissance aircraft on board).

At the end of October 1943, the first experimental Seyran was ready, flying the following month. In February 1944, the second aircraft was ready. The Seiran was a very elegant seaplane, with clean aerodynamic lines. Externally, it was very similar to the D4Y deck dive bomber. Initially, the D4Y was indeed considered a prototype for a new aircraft, but at the beginning design work this option was rejected. The unavailability of the AE1P Atsuta-32 engine determined the installation of the 1400-horsepower Atsuta-21. The test results have not been preserved, but they were apparently successful, since preparations for mass production soon began.

The first production M6A1 Seyran was ready in October 1944, seven more were ready by December 7, when an earthquake seriously damaged equipment and stocks at the plant. Production was almost restored when an American air raid on the Nagoya area followed on March 12. Soon it was decided to stop serial production of Seyran. This was directly related to the problems of building such large submarines. Although I-400 was ready on December 30, 1944, and I-401 a week later, it was decided to convert I-402 into an underwater transport, and production of I-404 was stopped in March 1945 at 90% completion. At the same time, production of AM type submarines was stopped and only I-13 and I-14 were completed. The small number of submarine aircraft carriers has consequently limited the production of submarine aircraft. Instead of the initial plans to produce 44 Seirans, only 14 were produced by the end of March 1945. Six Seirans were still produced before the end of the war, although many vehicles were at various stages of readiness.

At the end of autumn 1944, the Imperial Navy began training Seiran pilots, and flight and maintenance personnel were carefully selected. On December 15, the 631st Air Corps was created under the command of Captain Totsunoke Ariizumi. The corps was part of the 1st submarine flotilla, which consisted of only two submarines I-400 and I-401. The flotilla consisted of 10 Seirans. In May, submarines I-13 and I-14 joined the flotilla and were involved in the training of Seyran crews. During six weeks of training, the time to release three Seyrans from a submarine was reduced to 30 minutes, including the installation of floats, although in combat it was planned to launch aircraft without floats from a catapult, which required 14.5 minutes.

The initial target of the 1st flotilla was the locks of the Panama Canal. Six aircraft were to carry torpedoes and the remaining four bombs. Two aircraft were assigned to attack each target. The flotilla was to take the same route as Nagumo's squadron during the attack on Pearl Harbor three and a half years earlier. But it soon became clear that even if successful, such a raid was absolutely pointless in influencing the strategic situation in the war. As a result, on June 25, an order was issued to send the 1st Submarine Flotilla to attack American aircraft carriers at Ulithi Atoll. On August 6, I-400 and I-401 left Ominato, but were soon at the flagship due to short circuit a fire broke out. This forced the start of the operation to be postponed until August 17, two days before which Japan surrendered. But even after this, Japanese naval headquarters planned to attack on August 25th. However, on August 16, the flotilla received orders to return to Japan, and four days later to destroy all offensive weapons. On I-401, planes were ejected without starting engines and without crews, and on I-400 they were simply pushed into the water. Thus ended the story of the most unusual scheme for the use of naval aviation during the Second World War, interrupting history underwater aircraft for many years.

Tactical specifications M6A Seiran:

Type: two-seat submarine bomber

Engine: Atsuta 21, 12-cylinder liquid cooled, takeoff power 1400 hp, 1290 hp at an altitude of 5000 m

Weapons:

1 * 13 mm machine gun Type 2

1*850 kg torpedo, or 1*800 kg bomb, or 2*250 kg bombs

Maximum speed:

430 km/h at the ground

475 km/h at an altitude of 5200 m

Cruising speed - 300 km/h

Time to rise to altitude:

3000 m - 5.8 min

5000 m - 8.15 min

Ceiling - 9900 m

Flight range - 1200 km at a speed of 300 km/h and an altitude of 4000 m

Empty - 3300 kg

Take-off - 4040 kg

Maximum - 4445 kg

Dimensions:

Wingspan - 12.262 m

Length - 11.64 m

Height - 4.58 m

Wing area - 27 sq.m

Our days

The United States is currently working on the Cormorant aircraft.

American engineer L. Rail created the Cormorant project - a silent jet unmanned aerial vehicle based on a submarine, which can be equipped with both a melee weapon system and reconnaissance equipment.

Skunk Works, owned by Lockheed Martin, is developing an unmanned aircraft that will be launched from a submarine from an underwater position. Skunk Works is famous for developing the U-2 Dragon Lady and SR-71 Black Bird reconnaissance aircraft in the 1960s.

The new development is called Cormorant (cormorant). The aircraft will be able to launch from the Trident ballistic missile silo of Ohio-class submarines. These strategic missile carriers ceased to be in demand with the end Cold War, and now some of them are being converted into submarines for special operations.

The aircraft will be launched using a manipulator, which will bring it to the surface. After this, the drone will open its folded wings and be able to fly. It will land on the water, after which the same manipulator will return the aircraft aboard the submarine.

However, creating an aircraft that can withstand pressure at a depth of 150 feet, and at the same time light enough to fly, is not an easy task. Another difficulty is that submarines survive due to their silence, and a plane returning back to the boat can give away its location. Skunk Works' answer: a four-ton plane with gull wings that can fold along the plane's body so it can fit into a silo.

The design of the aircraft is durable - the body, made of titanium, is designed to withstand overloads that can occur at a depth of 45 meters, and all voids are filled with foam, which increases strength. The rest of the body is compressed by inert gas. Inflatable rubber seals protect weapon compartments, input devices engine and other aircraft parts. The geometry of the hull is made according to a complex design, which reduces its radio signature. The aircraft will be capable of performing reconnaissance or strike missions, depending on the equipment with which it will be equipped.

Thanks to the resource for the materials provided: feldgrau.info

More than a third of all losses submarine fleet The Third Reich in World War II had to rely on air attacks. PWhen enemy aircraft appeared, the boat had to urgently dive and wait out the danger in the depths. If there was no time left to dive, the submarine was forced to take on a battle, the outcome of which, however, was not always predetermined. An example is the incident in the Atlantic on January 6, 1944, when, northeast of the Azores, the submarine U 270 was attacked by a very unusual submarine hunter.

The struggle of two elements

During World War II, anti-submarine aircraft became German submarines the most dangerous enemy. According to the famous German historian Axel Niestlé, during the “Battle of the Atlantic”, out of 717 combat German submarines lost at sea, the Allied anti-aircraft aviation accounted for 245 sunk submarines. It is believed that 205 of them were destroyed by shore-based aircraft, and the remaining 40 were attributed to carrier-based aircraft. Death from air strikes ranks first on the list of causes of losses for the German submarine fleet, while PLO ships sank only 236 submarines. Another 42 submarines were sunk to the bottom through the joint efforts of ships and aircraft.

A common sight in the Atlantic during war is a submarine attacked by an aircraft. In the photo, U 118 is under fire from the Avengers from the aircraft carrier Baugh on June 12, 1943 - on this day the boat will be sunk by them

However, hunting German submarines from the air was not easy or safe, and the Allies lost more than 100 aircraft during the war in such attacks. The Germans, quickly realizing the threat of Allied air attacks, constantly improved the protection of their submarine ships, strengthening anti-aircraft artillery and installing detection and direction finding equipment for aircraft using radar.

Of course, the most reliable way for a submarine to survive a meeting with an aircraft was to evade combat. At the slightest threat of attack from the air, the boat had to urgently dive and wait out the danger at depth. If there was no time left to dive, the submarine was forced to take on a battle, the outcome of which, however, was not always predetermined. An example is the incident in the Atlantic on January 6, 1944, when, northeast of the Azores, the submarine U 270 was attacked by a very unusual submarine hunter.

Preparing the Fortress Mk.IIA bomber of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command for departure. Noteworthy is the memorable late version of camouflage, characteristic of Coastal Command aircraft - with camouflaged upper surfaces, the side and lower surfaces were painted white

Preparing the Fortress Mk.IIA bomber of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command for departure. Noteworthy is the memorable late version of camouflage, characteristic of Coastal Command aircraft - with camouflaged upper surfaces, the side and lower surfaces were painted white

In the summer of 1942, the British received 64 four-engine Boeing B-17s under Lend-Lease. Having had negative experience using the Flying Fortresses over Europe as a daylight bomber (20 early B-17Cs reached the UK back in 1941), they immediately assigned the new machines to RAF Coastal Command. It should be noted that in the UK, all American aircraft had their own designations, and by analogy with the B-17C, called Fortress Mk.I, the newly received 19 B-17F and 45 B-17E received the names Fortress Mk.II and Fortress Mk.IIA, respectively . In January 1944, both British Fortress squadrons, 206 and 220, were consolidated into 247 Coastal Air Group and were based at Lagens airfield on the island of Terceira in the Azores archipelago.

"Seven" vs. "Fortress"

After the disbandment of the German Borkum group (17 units) operating against allied convoys in the North Atlantic, three boats from its composition were to form one of the small groups called Borkum-1. It also included the above-mentioned U 270 of Oberleutnant zur See Paul-Friedrich Otto. The boats of the new group were supposed to take a position northwest of the Azores, but this particular area was within the operational area of the 247th Air Group.

Bombers from Coastal Command's 247th Air Group are scattered across an airfield in the Azores.

Bombers from Coastal Command's 247th Air Group are scattered across an airfield in the Azores.

On the afternoon of January 6 at 14:47, the Fortress with tail code “U” (serial number FA705) of Flight Lieutenant Anthony James Pinhorn from the 206th Squadron took off to search for and destroy enemy submarines. The plane did not return to base. The last message from him came at 18:16, after which the crew no longer contacted us. What happened to him? Entries from the surviving combat log of U 270 can tell about this.

On the evening of January 6, at 19:05, an airplane was spotted from a boat on the surface at a distance of 7,000 meters; the Vantse and Naxos electronic intelligence stations did not warn of its approach. The alarm was declared and anti-aircraft guns were prepared for battle. A few minutes later, the plane passed over the boat from the stern, but did not drop bombs, only firing at it from the tail turret. The shots from the “Fortress” did not harm U 270, which fired barrage from anti-aircraft guns. The plane repeated the approach, firing from machine guns, but again the bombs were not dropped. This time the aim was more accurate - the boat received several holes in the wheelhouse, its anti-aircraft gunners hesitated, and the plane avoided being hit.

U 270 crew officers on the bridge. In a white cap is the commander of the boat, Oberleutnant zur See Paul-Friedrich Otto. Visible on the horizon is an 85-meter-high monument to the memory of German sailors who died in the First World War. world war, installed on the coast in Laboe (neighborhood of Kiel)

U 270 crew officers on the bridge. In a white cap is the commander of the boat, Oberleutnant zur See Paul-Friedrich Otto. Visible on the horizon is an 85-meter-high monument to the memory of German sailors who died in the First World War. world war, installed on the coast in Laboe (neighborhood of Kiel)

Five minutes later, the “Fortress” attacked the “seven” for the third time from the stern. This time the “flaks” opened barrage fire in time, but the plane stubbornly walked straight towards the anti-aircraft guns. This was not in vain for him - the Germans managed to hit the right plane, and the engine closest to the fuselage caught fire. While passing over the boat, the plane dropped four depth charges set at shallow depth. The Seven made a sharp turn to port, and the bombs exploded approximately 30 meters from the bow of the boat. After a short period of time, the British plane, engulfed in flames, fell about 300 meters from U 270. The Germans did not find anyone at the crash site - the entire crew of the “Fortress” was killed. For this reason, the description of the battle exists only from the German side.

Recklessness vs recklessness?

The crew of the submarine acted harmoniously and courageously in a difficult situation; competent actions in controlling the boat and conducting anti-aircraft fire helped the Germans not only survive, but also destroy a dangerous enemy. However, despite the fact that the winners are not judged, it can be said that the commander’s decision not to dive was wrong, since at least 6 minutes passed from the moment the plane was discovered until its first attack. The boat emerged victorious from the battle, but received serious damage from bomb explosions and machine-gun fire and was forced to interrupt the voyage and return to base. One way or another, the crew of the British aircraft completed their main combat mission - albeit at such a high cost.

The famous German submariner Heinz Schaffer, in his memoirs, mentioned the tactics chosen by the commander of the U 445 boat on which he served when meeting with the plane:

“To increase readiness to repel aircraft raids, a siren was installed on the boat. It was turned on using a button located on the bridge next to the bell button. The decision on which signal to give - a bell to announce an emergency dive or a siren to announce an air raid raid - was made by the watch officer. A right or wrong decision meant a choice between life and death.

When an enemy aircraft could be detected in a timely manner, that is, at a distance of over four thousand meters, an urgent dive signal had to be given. The boat managed to dive to a depth of fifty meters before the plane approached the dive point and dropped bombs. If the top watch detected the plane at shorter distances, the attempt to dive almost inevitably led to the death of the boat.

The pilot of the aircraft, without being exposed to fire, could descend to a minimum altitude and carry out precise bombing at the stern of the boat, which was still on the surface or at a shallow depth. Therefore, if the aircraft was detected late, it was necessary to take the fight while remaining on the surface. In the zone of enemy air dominance, after the first plane that discovered the boat, reinforcements arrived, and attacks followed one after another. For this reason, there has always been a great temptation to avoid combat with aircraft by urgently diving, even in risky cases.”

If we rely on this tactic, then the commander of U 270, Paul-Friedrich Otto, had more time than the commander of U 445 left himself for a safe dive, but decided to take the fight. Probably, the commander of U 270 was confident in himself and his crew to take such a risk - perhaps completely unfounded. The boat paid for the victory over the British “Fortress” with serious damage to all bow torpedo tubes and the bow main ballast tank. On the way back to the base, she did not give more than 10 knots under diesel engines and upon arrival in Saint-Nazaire she was docked for two months of repairs.

The boat's anti-aircraft artillery is ready to fire. Two pairs of 20-mm anti-aircraft machine guns and a 37-mm gun are visible

The boat's anti-aircraft artillery is ready to fire. Two pairs of 20-mm anti-aircraft machine guns and a 37-mm gun are visible

A few words about the crew of the deceased bomber. There is no doubt that the long-range American bombers B-17 and B-24, supplied to the British, had good survivability, but they also had disadvantages that were fundamental for battles with submarines bristling with anti-aircraft guns. During the attack, the heavy bomber did not have sufficient maneuverability and was a good target for anti-aircraft gunners. If the boat could, with its maneuvers, bring the plane under its guns, then it was met with a barrage of lead - the pilots had to have enough courage to head straight for the anti-aircraft guns. There is a known case when a boat, attacked by two Liberators at once, held out against them for two hours. They even fired at the planes from a 105-mm deck gun, preventing them from accurately approaching the target and dropping bombs. It seems that in this case the pilots simply did not dare to climb directly onto the anti-aircraft gun barrels, but the crew of the “Fortress” that died in the battle with the U 270 turned out to be not timid. Three visits directly to the stern of the boat, where one or two twin 20-mm anti-aircraft guns and one 37-mm anti-aircraft gun were installed in the “winter garden”, can be called a feat.

The question remains why the British crew did not drop bombs on the first approach to the Otto submarine. Perhaps the reason was a malfunction of the bomb bays, but one cannot exclude the fact that Flight Lieutenant Pinhorn wanted to suppress enemy anti-aircraft points with machine-gun fire, and then drop bombs freely. However, the fire from the B-17 machine guns was ineffective - the boat did not suffer any casualties in the crew. Probably, dropping bombs in the first rounds could have been more effective, but, alas, history does not know the subjunctive mood.

Ground personnel from 53 Squadron Coastal Command unload 250kg depth charges before attaching them to the Liberator. This is exactly the aircraft that fell victim to the U 270 anti-aircraft gunners on the night of June 13-14, 1944

Ground personnel from 53 Squadron Coastal Command unload 250kg depth charges before attaching them to the Liberator. This is exactly the aircraft that fell victim to the U 270 anti-aircraft gunners on the night of June 13-14, 1944

In conclusion, I would like to mention that the entire “Fortresses” of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command scored 10 victories over German submarines, and they sank another submarine together with other types of aircraft. Already in April of the same 1944, the 206th squadron was re-equipped with the Liberators, which were more common in the Coastal Command, which had an advantage over the Fortresses in flight duration and bomb load.

As for the fate of U 270, on her next trip she scored another victory over the aircraft. This happened on the night of June 13-14, 1944 in the Bay of Biscay, when the boat's anti-aircraft gunners shot down the Liberator of the 53rd Squadron of the Royal Air Force, squadron leader John William Carmichael. U 270 found its destruction on August 13, 1944. The submarine was attacked by a Sunderland flying boat from the 461st Australian Squadron while it was evacuating people from Lorient and had 81 people on board including the crew. Lieutenant Commander Otto survived the death of his boat, as he had previously gone to Germany to receive the new “electric boat” U 2525. According to the authoritative website uboat.net, he may be alive to this day.

A painting by British artist John Hamilton depicts an attack by an anti-submarine Sunderland. The 461st Australian Squadron sank 6 German submarines using these vehicles.

A painting by British artist John Hamilton depicts an attack by an anti-submarine Sunderland. The 461st Australian Squadron sank 6 German submarines using these vehicles.

- pilot Flight Lieutenant Anthony James Pinhorn

- co-pilot Flight Officer Joseph Henry Duncan

- Navigator Flight Sergeant Thomas Eckersley

- Flight Officer Francis Dennis Roberts

- Warrant Officer Ronald Norman Stares

- Warrant Officer 1st Class Donald Luther Heard

- Warrant Officer 1st Class Oliver Ambrose Keddy

- Sergeant Robert Fabian

- squadron navigator, Flight Lieutenant Ralph Brown (was not part of the crew).

List of sources and literature:

- NARA T1022 (captured documents of the German fleet)

- Franks N. Search, Find and Kill – Grub Street the Basemenе, 1995

- Franks N. Zimmerman E. U-Boat Versus Aircraft: The Dramatic Story Behind U-Boat Claims in Gun Action with Aircraft in World War II – Grub Street, 1998

- Ritschel H. Kurzfassung Kriegstagesbuecher Deutscher U-Boote 1939–1945, Band 6. Norderstedt

- Busch R., Roll H.-J. German U-boat Commanders of World War II – Annopolis: Naval Institute Press, 1999

- Wynn K. U-Boat Operations of the Second World War. Vol.1–2 – Annopolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998

- Blair S. Hitler's U-boat War. The Hunted, 1942–1945 – Random House, 1998

- Niestlé A. German U-Boat Losses During World War II: Details of Destruction – Frontline Books, 2014

- Shaffer H. The last campaign of U-977 (translated from German by V.I. Polenina) - St. Petersburg: “Wind Rose”, 2013

- http://uboatarchive.net

- http://uboat.net

- http://www.ubootarchiv.de

- http://ubootwaffe.net

In many textbooks you can find mention of the appearance in 1963 of an unidentified flying object off the coast of California, USA. This fact cannot be refuted, since this is practically the only case in humanity when the appearance of a UFO was filmed.

But for many years, it remained a mystery what this mysterious object was and for what purpose it appeared off the coast of the United States. Today, in the era of declassification of CIA and KGB documents, we can say with confidence that there are real grounds to assert that the object that rose from under the water and soared into the air did not come from distant space, but is of entirely terrestrial origin. But is it?

Aircraft-submarine Conveir, 1964: this project could have become one of the most successful in the development of cruise submarines, if not for the resistance of US Senator Allen Elender, who unexpectedly closed the funding

Donald Reid's winged submarine Commander-2

Developed with the participation of the US Navy in 1964, this submarine in the form in which it is depicted in the diagram and drawing never existed in reality.

The first evidence that the object seen and filmed has a completely earthly origin can be found in the report of Richard Colen, who at that time worked as a deputy sheriff of the local police. That day he was on duty and in his report to management indicated that he managed not only to carefully examine the object, but also to film it. “This is definitely not a UFO. Outwardly, it is very similar to an airplane, so we can confidently say about its earthly origin,” Colin writes in the report.

Only after footage with sensational content spread all over the world, and Colin’s report only supplemented them, did the United States government put forward an official version of the appearance of an unidentified flying object. “A UFO off the coast of California is nothing more than an example of the secret developments of Soviet designers, and it was this device that the USSR military tested off the island of Catolina,” the White House press service said in response to numerous questions from journalists.

Charles Brown, an employee of the US Air Force Office of Special Investigations in 1965-1983, said the following: “In my opinion, this says only one thing - are we really behind the USSR in science? No, I do not think so. Maybe in this case we are witnessing an oversight or shortcoming of intelligence? I am sure of this." From the words of a person who took an active part in the investigation of the mysterious incident, we can conclude that in the United States at that time everyone was sure that the appearance of the object was the machinations of the USSR, and the main blame for the appearance of the Soviet object on its own shores was assigned to the intelligence department .

In turn, the USSR reacted extremely calmly to all statements of the US government. Did not have public speaking there were no ultimatums to refute the versions put forward by a political opponent; everything indicated that all statements from overseas had absolutely nothing to do with the Soviet Union. The information that our country is secretly developing completely new submarines was neither confirmed nor denied by the country's top leadership.

And now, when a significant part of the Soviet military archives was declassified and became available for review, researchers were able to establish that the mysterious object that American sailors encountered in the waters of the Pacific Ocean could indeed be the latest development Soviet designers.

Back in the 30s of the twentieth century, Soviet designers tried to build a unique design - a flying submarine (LPL).

The chief designer of a military facility unique in its technical characteristics was Vasily Ushakov, a talented Soviet designer whose name is associated great amount development of marine technical equipment for both military and civilian purposes. According to the designer's idea, the LPL should be shaped like an airplane, the body of which is made of a super-strong alloy. The LPL was supposed to rise to a height of up to 800 meters and, with the help of three engines, reach speeds of up to 300 km/h. It was assumed that the LPL would be able to travel vast distances by air, and then dive back into the water in a given square. Especially for this purpose, the designers provided hermetically sealed compartments to hide the engines. It took only 90 seconds to switch from flight mode and landing on water to complete immersion of the LPL.

“According to Ushakov’s plan, his submarine, taking into account the fact that the plane flies faster,” says Konstantin Kulagin, an expert historian of the USSR and Russian Navy, “should surface and instantly change position by air, which is extremely beneficial in confrontation with the enemy fleet.”

At the same time, Russian historians do not believe in the version that it was Ushakov’s submarine that surfaced off the coast of California in 1963. First of all, they point to the fact that there is no evidence that such a device was ever launched. It is obvious that Vasily Ushakov’s grandiose project remained a project on paper.

But if the USSR was never able to build an aircraft capable of launching from under water, then American designers coped with this task, and, it must be admitted, very successfully.

In 1975, the American concern Lockheed Martin introduced the world's first flying submarine. The newest ship Carmoran was capable of taking off into the air from a depth of 150 meters and accelerating to 400 km/h and at the same time, thanks to the Stealth system, remaining invisible to enemy radars. Thanks to its extremely low weight, the LPL performs maneuvers in the air that are beyond the capabilities of even modern conventional fighters. Carmoran's main task is to conduct reconnaissance and transmit data to the main ship or the main command center. To conduct reconnaissance, an unmanned vessel has all the necessary technical means, from video cameras to radio signal interceptors.

Today, the American LPL Carmoran is the only one in the world, but science does not stand still, and perhaps in the near future similar devices will appear in service with the Russian army. Or maybe they already exist?

This book is an attempt to take at least a cursory glance at some of the most original and confusing facts in the field. military history and, if possible, give them your own interpretation. This material should be considered only as a fairly well-founded version of the reasons that made the described events possible. It is up to the readers to decide how plausible these versions are. Another focus of the book is an attempt to bring together some of the most fantastic records set in the military sphere.

Submarine aviation

Submarine aviation

In military history, the statement that not a single bomb fell on the territory of the United States is a kind of axiom. However, this statement is not true. To prove this, let's take a short excursion into the practice of using aviation from... submarines.

Experience combat use The Kaiser's submarines at the beginning of the First World War revealed not only their brilliant qualities, but also a number of serious technical shortcomings. And first of all - the limitation of the review. Indeed, even when the submarine surfaced, only 10-12 miles of water surface was visible from the height of its wheelhouse. This, of course, is very small, especially when operating on ocean communications with single submarines of very large displacement, capable of staying at sea for more than 100 days.

Their autonomy was limited by the supply of torpedoes, so such submarines had strong artillery armament (150 mm), which made it possible to use torpedoes only as a last resort. For example, the world's first submarine of this class - the German U-155 - left Kiel on May 24, 1917, and returned only 105 days later. During the voyage, the boat covered 10,220 miles, of which only 620 were under water, and sank 19 ships (10 of them by artillery), which calmly followed their path without any cover.

The result of this raid, unprecedented in duration, was the forced expansion by the Entente countries of the area where convoys were used. In the report on the results of the campaign, the commander indicated that the main difficulty for the crew was the weeks of waiting for the target, even in areas with fairly busy shipping due to limited opportunity review.

And then the designers thought: how to raise the “eyes” of the boat? The answer suggested itself - try to equip the boat with an airplane. He could search for enemy ships, direct a submarine at them, ensure its communication with the squadron or base, remove the wounded, deliver spare parts and even protect the boat from enemy attacks. In general, the aircraft could certainly significantly improve the combat qualities of the submarine. However, the designers faced enormous technical difficulties. It was obvious that only a small floating, and collapsible, airplane was suitable for the submarine. But how to make a hangar on board, how will it affect the characteristics of the boat, especially its buoyancy, where and how to store fuel and supplies for the aircraft? In addition, it was necessary to overcome a psychological barrier: at that time the idea of a boat airplane sounded frankly fantastic, like flying to the moon. In practice, there were only isolated experiments in taking off aircraft from battleships, that is, the largest surface ships. Maybe this is another “fixed idea”? Only experiment could answer these questions.

In 1916, a series of giant submarine cruisers of the U-139-U-145 type, with a displacement of 2483 tons, a length of 92 m and a crew of 62 people, was laid down in Germany. Boat

was armed with two 150-mm guns, six 500-mm torpedo tubes, reached a speed of up to 15.3 knots and could travel 17,800 miles at an 8-knot speed. In the same year, the Hansa Brandenburg company received an order for an aircraft for this “underwater dreadnought”. This order was taken up by the young, but later world-famous designer E. Heinkel. Already at the beginning of 1918, tests began on the W-20, a small collapsible biplane boat with an 80 hp Oberursel engine. However, the car was far from shining with its data: speed of some 118 km/h, flight radius - 40 km, altitude - up to 1000 m, wingspan - 5.8 m, length - 5.9 m. True, assembly and disassembling the biplane took only 3.5 minutes, and it weighed only 586 kg.

The defeat of the Kaiser's Germany stopped all work on the construction of both submarines and aircraft for them. U-139, which had just entered service, was returned halfway from its first combat campaign and transferred as reparation to the French fleet, where it served safely until 1935.

The chief designer of German submarine cruisers, O. Flam, and a group of his engineers were invited to work in Japan, and American sailors became interested in boat aircraft. They contacted E. Heinkel and ordered two V-1 aircraft from the German Gaspar plant. They were supposed to be stored inside the boat, so the new plane was even smaller than the W-20: weighing 520 kg with a 60 hp engine, which provided a speed of 140 km/h. These experimental machines were never found in practical use, and in 1923 one of them was sold to Japan.

A year later, the Americans themselves built a similar aircraft - the Martin MS-1 - for the ocean-going submarine cruiser Argonaut, which entered service in 1925. In fact, the Americans simply improved the design of the captured U-139 without changing anything in principle. The ultra-light seaplane weighing 490 kg reached a speed of 166 km/h, but its assembly and preparation for flight took 4 hours, and disassembly even more. The submariners categorically refused such an assistant.

In 1926, another American “underwater” aircraft was ready - the X-2, which could take off from the Argonaut when it occupied a positional position. Pre-launch operations on this aircraft were completed in 15-20 minutes, but the submariners did not like this either: they did not take the aircraft into service and stopped all experiments of this kind. The Americans were finally convinced of the futility of collapsible aircraft and concluded that winged vehicles for submarines should be foldable and stored in a hangar.

The British took the baton in creating hydrofoils. In 1917-1918, the Grand Fleet was replenished with three unusual underwater monitors, boats armed with 12-inch guns taken from old ironclads. According to the Admiralty, these huge submarines with a displacement of 2000 tons were intended to support torpedo attacks and shelling of the coast. They had a length of 90 m, a crew of 65 people and could reach speeds of up to 15 knots. The idea did not pay off, and soon the lead boat M-1 was lost in an accident. They decided to re-equip the M-3

into an underwater minelayer, and the M-2 into an underwater aircraft carrier. The twelve-inch tank was dismantled, and in its place, near the wheelhouse, a light hangar was built, 7 m long, 2.8 m high and 2.5 m wide with a large hermetically sealed end hatch. When immersed in water, the hangar was filled with compressed air so that its walls could withstand the pressure.

The Admiralty offered to create an aircraft for an underwater aircraft carrier to the small company Parnel, which built sports airplanes. And on August 19, 1926, the Peto seaplane with a Lucifer engine with a power of 128 hp took off. Despite the modest dimensions of the vehicle (length - 8.6 m, wingspan - 6.8 m), its cabin accommodated two people - a pilot and an observer. After testing, a more powerful engine (185 hp) was installed on the second copy of “Peto” and the speed increased to 185 km/h. With its previous dimensions, the weight was 886 kg, and the flight altitude reached 3200 m. It was this machine, which earned high praise, that was accepted into service. True, tests that began in 1927 showed the very low efficiency of the system due to the very long time spent on takeoff, since the one initially removed from the Peto-2 was launched into the water using a rotary crane, and it ran up and took off on its own. Then a pneumatic catapult was installed on the boat, which instantly threw the plane into the sky. All this made it possible to reduce the take-off time to a quite acceptable 5 minutes. The experiment was considered successful and they began to think about its wider implementation...

On January 26, 1932, the M-2 submarine sank in the English Channel along with the Peto aircraft and the entire crew. When British divers descended to the scene of the disaster, they discovered that the hangar hatch was open. This tragic incident dealt a fatal blow to British submarine aviation.

The command of the Italian fleet also decided to acquire an underwater aircraft carrier. In 1928, a sealed hangar was built on the deck of the cruising boat Ettore Fierramosca, and the Macchi company next year built a small single-seat collapsible seaplane M-53 with a Citrus engine with 80 hp. Despite good results flight tests, the program was unexpectedly closed. It turned out that the modernized boat did not want to dive with an airplane on board, since the spacious hangar had too much buoyancy.

The French were doing more successfully. In 1929 they launched a giant submarine cruiser"Surcouf" with a displacement of 4300 tons and a length of 119.6 m. The boat was intended to guard Atlantic convoys and was supposed to engage in artillery combat with any raider such as an auxiliary cruiser, and attack warships with torpedoes. Therefore, the armament of the French submarine had no more analogues: it was equipped with armor, 203-mm turret guns, four 37-mm machine guns and 12 torpedo tubes (four internal bow and four twin external ones). To detect enemy raiders in a timely manner, the boat was equipped with a small reconnaissance seaplane. The crew of this giant submarine consisted of 150 people. Highest speed the speed reached 18 knots.

The aircraft hangar, 7 m long and 2 m in diameter, was located on the deck behind the wheelhouse. After the boat surfaced, the plane was brought to the stern, assembled, the engine was started, and the hatch to the hangar was battened down. The boat took a positional position (sank), the water washed away the plane, and the pilot began his takeoff run. At first, the Besson MV-5 with a 120-horsepower engine was based at Surcouf. The plane weighed 765 kg, developed a speed of 163 km/h and could rise to a height of 4200 m. The length of the machine was 7 m, the wingspan was 9.8 m. In 1933, it was replaced by a more advanced two-seater aircraft, the Besson MV-411, with the same motor. The weight of the car reached 1050 kg, length - 8 m, and wingspan - 11.9 m, but the technical characteristics were quite high: speed - 185 km/h; flight altitude - 1000 m, range - 650 km, and most importantly - assembly and disassembly took less than 4 minutes.

"Surcouf" served successfully until 1940. After the defeat of France, the boat went to England, where its crew joined the forces led by Charles de Gaulle. MV-411 flew several times for reconnaissance, but in 1941 it was seriously damaged and was no longer used. And on February 18, 1942, the Surcouf itself died in the Caribbean Sea - while guarding a convoy, it was rammed by a transport under its charge. There were no survivors...

In the Soviet Union, the famous creator of seaplanes, I. V. Chetverikov, began developing hydrofoils in the early 30s. For the K-series cruising boats, he proposed an aircraft that took up extremely little space and was called SIL. Representatives of the fleet liked the idea, and in 1933, construction began on the first version of the amphibian, which tested the design and ensured its stability on water and in the air.

At the end of 1934, the SPL was made, transported to Sevastopol, and naval pilot A.V. Krzhizhenovsky conducted tests. According to its design, the SPL was a two-seater flying boat with a free-supporting wing, above which was an M-11 engine with a pulling propeller. The tail unit, stabilizer and two fins were mounted on a special frame. The structure was made of wood, plywood, canvas and steel welded pipes. The empty weight of the aircraft was only 590 kg, and the take-off weight did not exceed 875 kg with two crew members. But the main advantage of the machine was the ability to quickly assemble and disassemble it. All this took less than 3 minutes. Assembly was carried out in reverse order in 3-4 minutes. At the same time, for joining the units, not traditional nuts and bolts were used, but quick-release pins.

After the Nazis came to power, the admirals of the Kriegsmarine remembered the exotic airplane created in 1918 by Heinkel. However, by this time the meter itself was busy with much more serious developments, so the development of the idea was entrusted to the Arado company, which by the beginning of 1940 built a single-seat float reconnaissance hydroplane Ar-231 with a 160 hp engine. The wingspan of this aircraft reached 10.2 m, length -

7.8 m, flight weight - 1050 kg, and it was placed in a hangar with a diameter of only 2 m. The plane picked up speed up to 180 km/h, but its ceiling did not exceed 300 m, but it could stay in the air for 4 hours, flying more than 500 km. It seemed good, but the assembly of the Ar-231 took about 10 minutes, which the sailors considered unacceptable. And then the designers tried to give the submariners another new product.

In 1942, specialists from the Focke-Angelis company came up with the Fa-330A tethered kite-gyroplane - an outwardly fragile structure, weighing 200 kg (including the pilot), consisting of a light frame with an observer’s seat and an instrument panel topped with a three-bladed rotor propeller. The units of the apparatus were stored in two steel cases on the deck of the boat and after 5-7 minutes they were turned into a finished product by three assemblers. The reverse procedure took only 2 minutes.

To launch this structure, the boat gained maximum speed, the propeller-rotor was spun by compressed air, and the kite obediently took off on a leash 150 m long to a height of about 120 m. In order for the motorless vehicle to hang in the sky, the submarine had to go at full speed all the time, without changing course, which sharply limited its maneuverability. In addition, the descent from maximum altitude could take more than 10 minutes, which put the submariners in a very dangerous position if an enemy aircraft was detected. And yet, despite these inconveniences, in 1943 the gyroplane was adopted and more than 100 copies were built, most of which were placed on boats in the Indian Ocean.

However, the Japanese have undoubtedly advanced the furthest in the creation of underwater aircraft. Methodically preparing for war on the oceans, Japanese intelligence was interested in all the new developments in the field of the navy and naval aviation. And therefore, it cannot be considered accidental that it was the Japanese who bought the German V-1 from America in 1923. In the mid-20s, Japan began designing huge ocean-going boats equipped with a reconnaissance aircraft. The six Yun-sen 1M class submarines that entered service in 1931-1932 had a displacement of 2,920 tons and a range of 14,000 miles; their armament consisted of two 150-mm guns and six torpedo tubes, and the crew numbered 92 people. A cylindrical hangar for a seaplane and a catapult for launching it were installed in the bow.

The aircraft was stored folded, and for its maintenance, access to the hangar was also available in an underwater position. The first Japanese submarine to receive an airplane was the I-5 submarine cruiser. These submarines were built to operate on ocean communications, and aircraft were built for reconnaissance and searching for targets, but events developed in such a way that these crumbs had to be used to solve completely different problems.

On April 18, 1942, several twin-engine aircraft approached Tokyo from the Pacific Ocean. Bombs rained down on the city and fires broke out.

It is clear that this raid was more a political demonstration than a military action. The fact is that long distances and the difficulty of taking off from aircraft carriers for coastal aircraft did not allow them to carry a significant bomb load. But Japan was then at the zenith of its power, and the raid on the capital of the empire was perceived as a slap in the face. The wounded samurai pride demanded revenge, but the country's technical capabilities clearly lagged behind the ambitious plans of its politicians.

On August 15, 1942, the submarine I-25 left the Yokosuka naval base for American shores, carrying an aircraft converted into an ultra-light bomber. A single-engine seaplane of the "ayagumos" type was accepted into the bow deck hangar of the submarine. The small and equally unreliable machine was fired into the air by a catapult and could make three-hour flights at a speed of 165 km/h.

Of course, the two 75-kilogram bombs that the plane could lift did not make it a formidable weapon of attack, and the lack of defensive weapons, the primitiveness of navigation equipment and low flight performance turned the pilot into a close resemblance to a kamikaze. But the command was confident that there would be no shortage of volunteers. The target of the attack, given the complete defenselessness of the "ayagumos", was chosen to be the deserted forests of America. One night, shortly before dawn, the I-25 surfaced off the coast of Oregon and launched its plane into the sky. An hour later the pilot, Captain Fujita, was convinced that he had reached his goal. The land of a formidable enemy, who boasted of his invulnerability, extended under the fabric surfaces of his plane. Fujita pressed the bomb release button and the phosphorus bombs flew down. A few minutes later, two columns of thick smoke rose above the forest, and an hour later, the “ayagumos” splashed down safely at the side of the submarine. On the same day, after sunset, the flight was repeated. However, this time it did not go so well, because on the way back the pilot got lost. Paradoxically, he was saved by the poor technical condition of the I-25: the boat left an oil trail behind itself, and it was along this trail that Fujita found it. The results of the raid were even better than the Japanese themselves expected: two severe fires broke out. The fire destroyed entire villages, killing several people. However, the use of “ayagumos” had to be abandoned: the Japanese understood perfectly well that the fact that Fujita got lost was not an accident. It was an accident that he managed to find the boat. They decided to repeat the raid using more advanced machines.

Since 1938, the Japanese fleet began to receive new boats of the Kaidai I series - powerful submarines with a length of 102 m, a displacement of 2440 tons, armed in addition to one 140-mm cannon and six torpedo tubes with two reconnaissance aircraft. The hangar and catapult stood in front of the wheelhouse. But by this time, the designers had created a two-seat biplane “Watabane-E9DC” with a “Hitahi Temp” engine with a power of 350 hp. and ten-meter wings folding back. Its dimensions were just right for the hangar of the new boat (though only one plane could fit there). The 1250-kilogram E9W1 had good flight data: maximum speed 233 km/h, ceiling 6750 m. It could stay in the air for more than 5 hours, but the service of this aircraft was short-lived: it was soon replaced by a more advanced monoplane E14W1, created by Yokosuka. The newcomers' baptism of fire occurred on December 7, 1942, when, taking off from the submarines I-9 and I-15, they filmed panoramas of the American base of Pearl Harbor,

had just been hit by Japanese naval aircraft. “Glen” (the bully), as these cars were nicknamed, weighed 1450 kg, the Hitahi Temp engine allowed it to reach speeds of up to 270 km/h and make five-hour flights. The armament consisted of a 7.7 mm turret machine gun, three 50 kg bombs and a full set of navigation equipment. In the absence of a second crew member, the bomb load could be increased to 300 kg.

In September 1942, I-9 and I-15 launched their planes off the coast of Arizona. This time, vehicles with red circles on their planes operated openly, causing quite a stir among ordinary people, who had already become accustomed to the fact that the fighting was taking place somewhere far away. in the other hemisphere. Of course, six 50-kg bombs were a purely symbolic blow, but it somewhat satisfied the samurai’s ambitions.

However, the main thing for the boat planes was reconnaissance: they made several effective reconnaissance flights over the territory of Australia and New Zealand, and the Glen with the I-15 even showed its red circles over Sydney. On May 31, 1942, an I-10 aircraft carried out reconnaissance of Diego Suarez Bay on the island of Madagascar, based on the data from which a successful attack on ships by midget submarines was carried out.

But for Admiral Yamomoto, an ardent admirer of naval aviation, reconnaissance alone was not enough. He planned to deal America a really serious blow - to disable the Panama Canal by bombing its locks. Bringing his plans to life, Japanese shipyards laid down super-submarines of the A1 series with a displacement of 4,750 tons. The lead one, the I-400, was intended for two aircraft, but then the hangar was rebuilt for three bombers. The Japanese succeeded

build three such submarine aircraft carriers, but they did not have time to distinguish themselves in battle: the war was over. And two years earlier, the Aihi company launched the M6A1 for testing - quite

modern bomb carrier "Seyran" ("Mountain Fog"). The car weighed 4925 kg and was equipped with a 1250 hp engine, which allowed it to reach a quite decent speed of 480 km/h. The length of the aircraft is 11.5 m, the wingspan is 12.5 m, the crew is 2 people, the bomb load is from 350 to 850 kg (with a minimum of fuel) or one torpedo. To launch the seaplane into the sky, a 40-meter pneumatic catapult was provided. In general, it was truly a real submarine aircraft carrier, but, fortunately for the Americans, it never got to fight.

Preparations for the raid on Panama began in February 1945 and were carried out with exceptional care. For training, mock-ups of the canal's locks were even built. However, the military situation was deteriorating, and the spectacular, but far from the most urgent, operation was postponed and postponed. Finally, they decided to carry it out, but at the same time solve a number of other problems. On August 25, a strike was planned on the Ulithi Atoll, and then the submarine aircraft carriers were supposed to head to Panama. On August 6, I-400 and I-401 went to sea, and it is difficult to predict how this voyage could end, but on August 16, the order came to surrender and return to base. The Seirans were ordered to be destroyed, and they were simply thrown overboard.

In the 1980s, the United States also put forward proposals to convert the nuclear submarine Helibad into an underwater aircraft carrier. For this purpose, it was planned to install a hangar for two Harrier vertical take-off and landing aircraft. However, so far not a single project of a modern underwater aircraft carrier has been implemented.

The aircraft detects the enemy from the air and delivers a disorienting strike. Then, having moved away from the line of sight, the car lands on the water and in a minute and a half plunges to a depth of several meters. The target is destroyed by an unexpected torpedo strike. In case of a miss, the device rises to the surface in two minutes and takes off to repeat the air attack. A combination of three such vehicles creates an impenetrable barrier for any enemy ship. This is how designer Boris Petrovich Ushakov saw his flying submarine

Editorial PM

Flight-tactical characteristics of LPL Crew: 3 people. // Take-off weight: 15,000 kg // Flight speed: 100 (~200) knots. (km/h) // Flight range: 800 km // Ceiling: 2500 m // Number and type of aircraft engines: 3 x AM-34 // Takeoff power: 3 x 1200 hp // Max. add. excitement during takeoff/landing and diving: 4−5 points // Underwater speed: 4−5 knots // Dive depth: 45 m // Cruising range under water: 45 miles // Underwater endurance: 48 hours // Propeller motor power: 10 hp // Dive duration: 1.5 min // Ascent duration: 1.8 min // Armament: 18-in. torpedo: 2 pcs. coaxial machine gun: 2 pcs.

Donald Reid's winged submarine Commander-2 Developed with the participation of the US Navy in 1964, this submarine in the form in which it is depicted in the diagram and drawing never existed in reality.

Aircraft-submarine Conveir, 1964: this project could have become one of the most successful in the development of cruise submarines, if not for the resistance of US Senator Allen Elender, who unexpectedly closed the funding

The unmanned aircraft-submarine The Cormorant, developed by Skunk Works (USA) and tested as a full-size model in 2006. All details about this project are hidden under the heading “top secret”

Of course, such a project could not fail to appear. If there is an amphibious vehicle, why not teach a plane to dive under water? It all started in the 30s. Second-year cadet at the Higher Naval Engineering School named after. F.E. Dzerzhinsky (Leningrad) Boris Petrovich Ushakov embodied on paper the idea of a flying submarine (LPL), or, rather, an underwater aircraft.

In 1934, he provided a voluminous folder of drawings along with a report to the department of his university. The project “walked” through the corridors, departments and classrooms of the school for a long time, and was classified as “secret”; Ushakov more than once modified the design of the submarine in accordance with the comments received. In 1935, he received three copyright certificates for various components of his design, and in April 1936 the project was sent for consideration to the Scientific Research Military Committee (NIVK, later TsNIIVK) and at the same time to the Naval Academy. A detailed and generally positive report on Ushakov’s work, prepared by Captain 1st Rank A.P., played a major role. Surin.

Only in 1937, the project was endorsed by the NIVK professor, head of the department of combat tactics, Leonid Egorovich Goncharov: “It is advisable to continue the development of the project in order to reveal the reality of its implementation,” the professor wrote. The document was also studied and approved by the head of the NIVK, military engineer of the 1st rank, Karl Leopoldovich Grigaitis. In 1937-1938, the project nevertheless continued to “walk” along the corridors. Nobody believed in its reality. At first he was included in the work plan of department “B” of the NIVK, where, after graduating from college, Ushakov entered as a military technician of the 1st rank, then he was excluded again, and the young inventor continued his work on his own.

Airplane aquarium

The aircraft-submarine gradually acquired its final appearance and "stuffing". Externally, the device looked much more like an airplane than a submarine. An all-metal machine weighing 15 tons with a crew of three people was theoretically supposed to reach speeds of up to 200 km/h and have a flight range of 800 km. Speed under water is 3-4 knots, diving depth is 45 m, swimming range is 5-6 km. The aircraft was to be powered by three 1000-horsepower AM-34 engines designed by Alexander Mikulin. Superchargers allowed the engines to perform short-term boosts with an increase in power up to 1200 hp.

It is worth noting that at that time AM-34s were the most promising aircraft engines produced in the USSR. The design of the 12-cylinder piston power unit largely anticipated developments aircraft engines well-known companies“Rolls-Royce”, “Daimler-Benz” and “Packard” - only the technical “closeness” of the USSR prevented Mikulin from gaining worldwide fame.

Inside, the plane had six sealed compartments: three for engines, one for living quarters, one for the battery and one for the 10 hp electric propulsion motor. The living compartment was not a pilot's cabin, but was used only for scuba diving. The pilot's cabin flooded during the dive, as did a number of leaky compartments. This made it possible to make part of the fuselage from lightweight materials that were not designed for high pressure. The wings were completely filled with water by gravity through scuppers on the flaps to equalize the internal and external pressure.

The fuel and oil supply systems were turned off shortly before full immersion. At the same time, the pipelines were sealed. The aircraft was covered with anti-corrosion coatings (varnish and paint). The dive took place in four stages: first, the engine compartments were battened down, then the radiator and battery compartments, then the control switched to underwater, and finally, the crew moved into the sealed compartment. The aircraft was armed with two 18-inch torpedoes and two machine guns.

On January 10, 1938, the project was re-examined by the second department of the NIVK. Nevertheless, everyone understood that the project was “crude” and huge amounts of money would be spent on its implementation, and the result could be zero. The years were very dangerous, there were massive repressions, and it was possible to fall under the hot hand even for accidentally dropping a word or using the “wrong” surname. The committee put forward a number of serious comments, expressing doubts about the ability of Ushakov’s plane to take to the skies, catch up with a departing ship under water, etc. To divert attention, it was proposed to make a model and test it in a pool. There are no further mentions of the Soviet aircraft-submarine. Ushakov worked for many years in shipbuilding on ekranoplanes and ships on air wings. All that was left of the flying boat were diagrams and drawings.

Engine under the hood

A project similar to Ushakov’s in the USA appeared many years later. As in the USSR, its author was an enthusiast whose work was considered crazy and unrealizable. A fanatical designer and inventor, electronics engineer Donald Reid has been developing submarines and creating their models since 1954. At some point, he came up with the idea of building the world's first flying submarine.

Reid collected a number of models of flying submarines, and when he was convinced of their performance, he began assembling a full-fledged device. To do this, he mainly used parts from decommissioned aircraft. Reid assembled the first copy of the Reid RFS-1 aircraft-submarine by 1961. The aircraft was registered as aircraft number N1740 and was powered by a 65-horsepower 4-cylinder Lycoming aircraft engine. In 1962, the RFS-1 aircraft, piloted by Donald's son Bruce, flew 23 m above the surface of the Shrewsbury River in New Jersey. Immersion experiments could not be carried out due to serious design flaws.