Various classifications of transaction costs. Classification of transaction costs according to North Eggertson Basic approaches to the classification of transaction costs

According to Commons, a transaction is not an exchange of goods, but an alienation and appropriation of property rights and freedoms created by society. This definition makes sense (according to Commons) because institutions ensure that the will of an individual extends beyond the area within which he can influence environment directly by their actions, i.e. beyond the scope of physical control, and therefore turn out to be transactions, as opposed to individual behavior as such or the exchange of goods.

Commons distinguished three main types of transactions:

1. The transaction of the transaction serves to carry out the actual alienation and appropriation of property rights and freedoms, and its implementation requires mutual consent of the parties, based on the economic interest of each of them.

In the transaction, the condition of symmetrical relations between counterparties is observed. Distinctive feature The transaction of the transaction, according to Commons, is not production, but the transfer of goods from hand to hand.

2. Management transaction – the key here is the relationship of subordination management, which involves such interaction between people when the right to make decisions belongs to only one party. In a management transaction, behavior is clearly asymmetrical, which is a consequence of the asymmetry of the position of the parties and, accordingly, the asymmetry of legal relations.

3. Rationing transaction - in this case, the asymmetry of the legal status of the parties is preserved, but the place of the managing party is taken by a collective body that performs the function of specifying rights. Rationing transactions include: the preparation of a company budget by the board of directors, the federal budget by the government and approval by a representative body, the decision of an arbitration court regarding a dispute arising between operating entities through which wealth is distributed. There is no control in the rationing transaction. Through such a transaction, wealth is allocated to one or another economic agent.

The presence of transaction costs makes certain types of transactions more or less economical depending on the circumstances of time and place. Therefore, the same operations can be mediated various types transactions depending on the rules that they order.

The concept of transaction costs was introduced by R. Coase in the 1930s in his article “The Nature of the Firm.” It has been used to explain the existence of hierarchical structures that are antithetical to the market, such as firms. R. Coase associated the formation of these “islands of consciousness” with their relative advantages in terms of saving on transaction costs. He saw the specifics of the company's functioning in the suppression of the price mechanism and its replacement with a system of internal administrative control.

According to Coase, transaction costs are interpreted as “the costs of collecting and processing information, the costs of negotiations and decision-making, the costs of monitoring and legal protection of the implementation of the contract.”

Within the framework of modern economic theory, transaction costs have received many interpretations, sometimes diametrically opposed.

Thus, K. Arrow defines transaction costs as the costs of operating an economic system.

Many economists use an analogy with friction when explaining the phenomenon of transaction costs. Coase has a reference to Stigler's words: Stigler said of the “Coase theorem”: “A world with zero transaction costs turns out to be as strange as a physical world without friction forces. Monopolists could be compensated to behave competitively, and insurance companies would simply not exist.”

Based on such assumptions, conclusions are drawn that the closer an economy is to the Walrasian general equilibrium model, the lower its level of transaction costs, and vice versa.

In D. North’s interpretation, transaction costs “consist of the costs of assessing the useful properties of the object of exchange and the costs of ensuring rights and enforcing their observance.” These costs inform social, political, and economic institutions.

G. Demsets understands this category of costs “as the costs of any activity associated with the use of the price mechanism. Similarly, he defines management costs as “costs associated with conscious management of the use of resources” and proposes to use the following abbreviations: PSC (price system costs) and MSC (management system costs) - respectively, the costs of using the price mechanism and the management mechanism.

Also in the New Institutional Economic Theory (NIET), the following view of the nature of transaction costs is common: “The fundamental idea of transaction costs is that they consist of the costs of drafting and concluding a contract ex ante, as well as the costs of supervising compliance with the contract and enforcing its implementation ex post as opposed to production costs, which are the costs of actually fulfilling the contract. To a large extent, transaction costs are relations between people, and production costs are costs of relations between people and things, but this is a consequence of their nature rather than their definition.”

In the theories of some economists, transaction costs exist not only in a market economy (Coase, Arrow, North), but also in alternative ways economic organization and, in particular, in a planned economy (S. Chang, A. Alchian). Thus, according to Chang, maximum transaction costs are observed in a planned economy, which ultimately determines its inefficiency.

2. Classifications of transaction costs

A significant number of types of classifications of transaction costs is a consequence of the multiplicity of approaches to the study of this problem. O. Williamson distinguishes two types of transaction costs: ex ante and ex post. Ex ante costs include the costs of drafting the agreement and negotiating it. Ex post costs include organizational and operational costs associated with the use of the governance structure; costs arising from poor adaptation; costs of litigation arising in the course of adapting contractual relations to unforeseen circumstances; costs associated with fulfilling contractual obligations.

K. Menard divides transaction costs into 4 groups:

Isolation costs;

Costs of scale;

Information costs;

Costs of behavior.

In the functioning of any organization, there is, first of all, the problem of inseparability, and the total costs of separation arise precisely for this reason. In most cases economic activity achieved through joint efforts, but it is impossible to accurately measure ultimate performance each factor involved and its reward. K. Menard gives the example of a team of loaders: “To set the wages of the team, using the organization turns out to be more effective than using the market. The organization surpasses the market even when the latter requires too detailed, otherwise impossible, differentiation.”

Further, K. Menard highlights the costs of scale. The larger the scale of the market, the more impersonal the acts of exchange are, and the more necessary it is to develop institutional mechanisms that determine the nature of the contract, the rules for its application, sanctions for non-compliance with obligations, etc. Conclusion employment contracts Designed to stabilize the relationship between employer and employee, supply contracts - to ensure the regularity of the flow of costs - are partly explained by the need to establish "trust, which the scale of markets and periodic contracting would make both problematic and expensive."

Information costs represent a separate category. The transaction is related to information system, whose role is modern economy the price system plays a role. This category includes costs that cover all aspects of the functioning of an information system: coding costs, signal transmission costs, training costs to use the system, etc. Every system, through its functioning, creates various interferences, which reduce the accuracy of price signals. The latter cannot be too differentiated, since the manipulation of a very large number of signals is associated with prohibitive costs. The organization in this case allows you to reduce costs by using less of the market and limiting the number of signals sent and received.”

The last group consists of behavioral costs. They are associated with “selfish behavior of agents”; a similar concept accepted and used now is “opportunistic behavior.”

The most famous domestic typology of transaction costs is the classification proposed by R. Kapelyushnikov:

1. Costs of searching for information. Before a transaction is made or a contract is concluded, you need to have information about where to find potential buyers and sellers of relevant goods and factors of production, what are the current prices. Costs of this kind consist of the time and resources required to conduct the search, as well as losses associated with the incompleteness and imperfection of the acquired information.

2. Negotiation costs. The market requires the diversion of significant funds for negotiations on the terms of exchange, for the conclusion and execution of contracts. The main tool for saving this kind of costs is standard (standard) contracts.

3. Measurement costs. Any product or service is a set of characteristics. In the act of exchange, only some of them are inevitably taken into account, and the accuracy of their assessment (measurement) can be extremely approximate. Sometimes the qualities of a product of interest are generally immeasurable, and to evaluate them one has to use surrogates (for example, judging the taste of apples by their color). This includes the costs of appropriate measuring equipment, the actual measurement, the implementation of measures aimed at protecting the parties from measurement errors and, finally, losses from these errors. Measurement costs increase with increasing accuracy requirements.

Enormous savings in measurement costs have been achieved by mankind as a result of the invention of standards for weights and measures. In addition, the goal of saving these costs is determined by such forms of business practices as warranty repair, branded labels, purchasing batches of goods based on samples, etc.

4. Costs of specification and protection of property rights. This category includes the costs of maintaining courts, arbitration, government agencies, the cost of time and resources required to restore violated rights, as well as losses from their poor specification and unreliable protection. Some authors (D. North) add here the costs of maintaining a consensus ideology in society, since educating members of society in the spirit of observing generally accepted unwritten rules And ethical standards is a much more economical way to protect property rights than formalized legal control.

5. Costs of opportunistic behavior. This is the most hidden and, from the point of view of economic theory, the most interesting element of transaction costs.

There are two main forms of opportunistic behavior. The first is called moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs when one party in a contract relies on another party, and obtaining actual information about his behavior is costly or impossible. The most common type of opportunistic behavior of this kind is shirking, when the agent works with less efficiency than is required of him under the contract.

Particularly favorable conditions for shirking are created in conditions of joint work by a whole group. For example, how to highlight the personal contribution of each employee to the overall result of activities<команды>factory or government agency? We have to use surrogate measurements and, say, judge the productivity of many workers not by results, but by costs (such as labor time), but these indicators often turn out to be inaccurate.

If the personal contribution of each agent to the overall result is measured with big mistakes, then his remuneration will be weakly related to the actual efficiency of his work. Hence the negative incentives that encourage shirking.

In private firms and government agencies, special complex and expensive structures are created whose tasks include monitoring the behavior of agents, detecting cases of opportunism, imposing penalties, etc. Reducing the costs of opportunistic behavior is the main function of a significant part of the management apparatus of various organizations.

The second form of opportunistic behavior is extortion. Opportunities for him appear when several production factors They work in close cooperation for a long time and get used to each other so much that everyone becomes indispensable and unique to the other members of the group. This means that if some factor decides to leave the group, then the remaining participants in the cooperation will not be able to find an equivalent replacement on the market and will suffer irreparable losses. Therefore, the owners of unique (in relation to a given group of participants) resources have the opportunity for blackmail in the form of a threat to leave the group. Even when “extortion” remains only a possibility, it always turns out to be associated with real losses. (The most radical form of protection against extortion is the transformation of interdependent (interspecific) resources into jointly owned property, the integration of property in the form of a single bundle of powers for all team members).

In a market economy, a company’s costs can be divided into three groups: 1) transformational, 2) organizational, 3) transactional.

Transformation costs – costs of transformation physical properties products in the process of using production factors.

Organizational costs are the costs of ensuring control and distribution of resources within the organization, as well as the costs of minimizing opportunistic behavior within the organization.

Transaction and organizational costs are interrelated concepts; an increase in some leads to a decrease in others and vice versa.

3. Transaction costs and institutions

The role of institutions in a market economy is to reduce transaction costs. Minimizing transaction costs leads to increased competition market structure and, consequently, in most cases, to an increase in the efficiency of the functioning of the market mechanism. The presence of institutional barriers to competition between business entities leads to the opposite result. Therefore, their study assumes a clear substantive description of the category “competition”.

As D. North and J. Wallis have shown, the development of market relations in a transition economy determines the emergence and development of the transaction sector. According to their interpretation, the transaction sector includes industries whose main function is to ensure the redistribution of resources and products with the lowest average transaction costs.

In developed countries, there is a tendency to reduce specific transaction costs, which determines an increase in the number of transactions, and therefore the volume of total costs in the economy may increase. However, in Russia, due to the existence of ineffective institutions, administrative barriers and restrictions, average transaction costs remain at an unacceptably high level, which limits the volume and number of transactions, leading to an increase in the marginal costs of enterprises exposed to them.

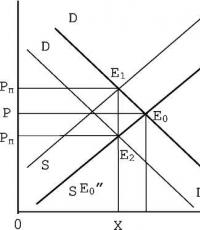

Thus, the impact of growing transaction costs on market equilibrium is carried out through the mechanism of introducing additional taxes. As can be seen from Figure 1, in the market for an individual product this leads to an increase in price and a decrease in sales volumes. This position of the model is consistent with the realities of economic practice in Russia, where relatively high prices are observed in comparison with the income of the population.

Figure 1. Shifting equilibrium under the influence of rising transaction costs

The higher the level of transaction costs TC, the greater the shift in the supply curve.

The use of transaction costs as a tool of economic analysis provides opportunities for interpreting institutional equilibrium and its modification in a transition economy.

Demand for institutions comes from individuals, groups, or society as a whole, since the social or group costs of creating and maintaining an institution should be less than the costs that arise in its absence. The value of transaction costs becomes not only a quantitative indicator of the degree of market imperfection, but also a quantitative expression of the costs of the absence of an institution. Therefore, the higher the transaction costs, the higher the demand for institutional regulation, which complements and even replaces market regulation.

According to modern institutional theory, the effectiveness of the functioning of a particular institution is determined by the amount of savings on transaction costs. Therefore, the costs of engineering institutions in the labor market by society will be correlated with the value of transaction costs (ATC), which allows us to express through them the demand function for institutions, and collective action costs (CAC), which characterize the supply of institutions “in the institutional market.” The process of establishing institutional equilibrium is presented in Figure 2 (N is the number of individuals included in the sphere of action of institutions, AIC is institutional costs - transaction costs, the reduction of which is ensured by institutions, and the costs of creating institutions).

Rice. 2. Institutional balance

In the presented traditional model of institutional equilibrium, the fundamental nature may be different degrees of bargaining power of the parties, if we consider the whole society from the demand side for institutions, and from the supply side - the state as a monopolist, producing formal institutions and not only enforcing the implementation of the rules and norms it establishes , but also by virtue of this, as well as certain control over information flows, shaping public opinion.

It is beneficial for the state to carry out a kind of price discrimination in the institutional market, i.e. limit access to certain rights and institutionalized forms of economic activity based on group affiliation. In turn, this determines both the methods of generating income and their amount, depending on the “price” paid in the form of overcoming barriers expressed in high transaction costs of using institutions.

Thus, adjusting the model of a competitive market of institutions in a transition economy consists of taking into account the monopoly power of the state offering formal institutions on the institutional market, which has a significant impact on the asymmetry of income distribution.

Rice. 3. Modification of institutional equilibrium

In this case, the demand and supply curves of institutions change their shape and slope. The supply curve (or the collective action cost curve, i.e. the social costs of creating institutions, collective action cost - CAC) becomes horizontal, since the creation of an institution is associated with fixed costs for maintaining the state apparatus. The demand curve (or aggregate transaction cost curve - ATC) takes on a positive slope due to the distributive nature of the institutions being created. Therefore, with an increase in the number of individuals included in its sphere of action (N), their comparative benefits decrease due to an increase in transaction costs that block entry into the distribution of certain benefits.

Thus, the existence of a monopoly on institutions is manifested in the differentiation of access to opportunities for economic activity depending on the criteria that are significant under a particular government system. This, in turn, determines the distribution of income, creating advantages for certain groups to receive them, but at the same time blocking them for the rest of the population.

Money and its functions.

Money and its functions

Introduction

The Russian monetary system is an important area national economy, where in last years radical changes are taking place. The system is changing radically, new forms of payments are being introduced, the relationship between banks and their clients is changing, and new proportions between finances are emerging.

Against the backdrop of actively developing commodity and financial markets, the role of money is growing sharply. The situation in the transition economy and the formation of the market require the search for new forms of monetary relations.

The complex changes caused by the transition from a monopolized loan fund and the entire banking system, previously managed by administrative-command methods, to a new market organization of the economy can only be correctly understood and taken into account on the basis of a number of theoretical provisions about the nature of money, as well as historical experience.

Functions of money

The time has passed when many believed that money was gold, a special commodity that stood out from the mass of all goods, possessing special properties that were very convenient for performing monetary functions.

Money as a measure of value is used to measure and compare the cost of various goods and services. In accordance with this function, each country sets its own price scale, that is, a national measure of value

(in Russia - ruble, in Germany - mark, etc.)

The price scale is a means of expressing value in monetary units, a technical function of money. In metal circulation, when the metal - a monetary commodity - performs the functions of money, the scale represents the weight amount of the monetary metal accepted in the country as a monetary unit or multiples. States fixed the scale of prices by law.

When money is used to purchase goods and pay for services, it functions as a medium of exchange. This role is fleeting, but very important. Being a universal equivalent, money allows for the purchase and sale of a variety of goods, they are accepted by every seller and provide universal purchasing power (in contrast to barter transactions, in which there is a direct exchange of goods for goods without the participation of money). Thanks to this function, the owner of the money has the opportunity to choose sellers, time, place and range of goods purchased. The function of money as a means of payment is manifested in the fact that money is also used to pay off various kinds of obligations (for wages, taxes, cash loans, in connection with insurance, administrative and judicial payments, etc.) Payment is made by transferring one a participant in the economic turnover of money to another, acting as an independent form of value.

A characteristic feature of the functioning of money as a means of payment when paying obligations for goods and transactions is that here payment is made not in cash, but through non-cash transfers, i.e. accounting records (money is debited from the payer’s bank account and credited to the supplier’s bank account). Money as a means of payment provides charges for payment wages.

Money also acts as a means of storage. It consists of preserving the value generated after the sale of goods and services, for making purchases in the future. Of course, not only money can be represented in the form of savings, but also precious metals, precious stones, buildings, securities. However, the use of money in this function is most convenient, since it is the most liquid form of savings.

In other forms of savings, liquidity is present to a lesser extent.

Money is widely used in foreign economic relations. Here they function as world money. In the modern world, money is represented by credit banknotes.

Let us explain the differences between the concept of “credit banknotes” and the term

"paper money. Credit banknotes can also be made of paper; in their economic essence they are “not paper”; behind them in the economy there are real material values or useful costs. These are banknotes, credit instruments of circulation. Banks issue them in the process of performing credit transactions.

Law of money circulation

The number of banknotes required for circulation is determined by the economic law of monetary circulation. In accordance with this law, the amount of money needed at any given moment for circulation can be determined by the formula:

D=(C-V+P-VP)/S.O., where

D – the number of monetary units required for circulation in a given period;

C – the sum of prices of goods to be sold;

B – the sum of prices of goods for which payments extend beyond the given period;

P – the sum of the prices of goods sold in previous periods, the payment terms for which have come;

VP – the amount of mutually extinguishable payments;

S.O. – rate of turnover of a monetary unit.

In simplified form, this formula can be represented as follows:

D=MxC/S.o., where

M – mass of goods sold;

C – average price of goods;

S.o. – average turnover rate (how many times a ruble turns over a year).

Transforming this formula, we obtain the exchange equation:

DxS.O.=MxC, which means that the product of the quantity of money by the velocity of circulation is equal to the product of the level of money by the commodity mass. When crisis phenomena arise in the economy, this equality is violated and money depreciates, which can be expressed in the formula:

DxS.o.>MxC

Such depreciation, or “inflation” (from the Latin inflatio - inflation), means a drop in the price of money due to excess emission

Banknotes, increasing their quantity necessary for normal turnover. Inflation leads to rising prices and a redistribution of gross product and wealth in favor of state monopoly enterprises and the shadow economy at the expense of maintaining real wages and other incomes of the general population. Inflation occurs in various forms and is influenced by many factors. Considering the forms of inflation in an enlarged form, we can distinguish two: obvious inflation, manifested in open price increases, and hidden, indirect. The first form is visible on the surface of the phenomena, and the second consists in the depreciation of money, when the increase in prices is hidden (the quality of goods decreases, new goods produced have an inflated price that does not correspond to consumer properties, due to a lack of monetary resources, the payment of wages and other payments is delayed).

The main factors causing inflation are the release of excess money supply into circulation, a drop in production volumes, imbalances in the development of economic sectors, a budget deficit, a lag in the production of goods from effective demand and other negative phenomena. These imbalances can increase under the influence of incorrect economic policies of enterprises, firms, banks and the state.

In Russia, during the transition to a market economy, the level of inflation is affected by: the state budget deficit and an increase in public debt; overinvestment; unreasonable increases in prices and wages; credit expansion - expansion of credit without taking into account its depreciation, which leads to the issue of money in various forms; excessive emission of money in cash; excess money emission, perpetuating price increases resulting from incorrect pricing policies; strengthening the role external factors through the mechanism of currency convertibility, when there is an increase in prices for imported goods; exchange of foreign currency for national currency, which is the basis for additional money emission, since additional funds appear in bank deposit accounts.

Inflation can be creeping and galloping. With “creeping” inflation, prices rise slowly, while with galloping inflation, prices rise rapidly and spasmodically. As the crisis deepens, inflation turns from a temporary factor in economic revival into a sharply negative factor, reducing production and increasing socio-economic instability in the country. At the same time, economic relations are disorganized, there is an outflow of funds and personnel into profitable industries, speculation and the shadow economy are intensified, and corruption is growing.

The situation in the economy is further aggravated by the fact that so-called inflationary expectations arise, there is a “flight” from money, and excess reserves are created in the economy and among the population.

Like Commons, in neo-institutional theory the basic unit is recognized as an act of economic interaction, a deal, a transaction, which is an exchange of bundles of property rights. And, therefore, transaction costs (or costs of its implementation) arise when individuals exchange property rights and cover activities related to this process. These types of activities include:

- searching for information on prices and quality, as well as searching for potential buyers and sellers and information about their reputation;

- trading necessary to identify the true positions of counterparties;

- supervision of contract partners and ensuring conditions for fulfilling the terms of the contract, collecting damages if necessary;

- protection of property rights from encroachment by a third party.

And according to these types of activities accompanying the transaction, types (or elements) of transaction costs are distinguished.

The costs of searching for information, or the costs of identifying alternatives. In conditions of uncertainty that exists in any real economic system, costs inevitably arise due to the search for the most favorable price and other contract terms. It is quite obvious that before a transaction is made or a contract is concluded, it is necessary to have information about where potential buyers and sellers of the relevant goods and factors of production can be found, what are the current prices, etc. Costs of this kind consist of the time and resources required to conduct the search, as well as losses associated with the incompleteness and imperfection of the acquired information. As already emphasized, the uncertainty existing in the market, which generates asymmetry of information possessed by counterparties, is the most important reason for the emergence of transaction costs. Trying to level out this asymmetry, they incur the costs of searching, accumulating and verifying information.

To minimize this type of costs, institutions such as exchanges, as well as advertising or reputation are used. Reputation as a socially significant assessment of an economic agent from the point of view business ethics, helps to save transaction costs. It is closely related to the means of individualization of enterprises, in particular with brand names and trademarks. It is these tools that allow consumers to save on search costs. True, this means that the stronger trademark is a source of information and the greater the savings on search costs, the higher, other things being equal, the price that the seller can charge.

As for the institution of exchanges, which are a type of organized markets, cost savings are possible due to the concentration of supply and demand in space and (or) time. As a result, the circulation of information accelerates and prices are more intensively equalized.

A type of information search cost is measurement cost. Costs of this kind are associated with the fact that any product or service is a complex of characteristics, and in the act of exchange only some of them are inevitably taken into account, and the accuracy of their assessment (measurement) can be extremely approximate. Sometimes the qualities of a product of interest are generally immeasurable, and to evaluate them one has to use surrogates. Measurement costs increase with increasing accuracy requirements. These measurements consist of determining certain physical parameters of the exchanged rights (color, size, weight, quantity, etc.), as well as determining property rights (use rights, rights to receive and alienate income).

As a consequence, one of the most important problems market practice becomes the problem of measuring the quality of goods and services. In connection with the definition of this type of transaction costs, three categories of goods are distinguished: experienced, researched, and trust. Goods with prohibitively high costs of measuring quality before purchasing them are called experienced goods. Goods with a relatively cheap procedure for preliminary determination of quality are called research goods. The quality of the latter can be relatively easily assessed before purchase.

The quality of goods of the second type (research) can be established by inspection prior to purchase, while the quality of goods belonging to the first type (experimental) can only be determined during the process of using this product. Note here that in markets where sellers have little to gain from investing in reputation, they may lack incentives to supply high-quality, empirically assessed goods. In that case, if we're talking about about the organization of the market for an experienced durable good, a set of signals is of great importance. For example, warranty after-sales service, the ability to replace defective goods within a certain period, etc. Warranty after-sales service serves as a kind of insurance for the buyer, involving the transfer of risk to the seller.

As for trust goods, they are characterized by high measurement costs both before and after purchase. This is due to the difficulty of calculating the positive effect due to the complexity of assessing the result obtained. Fiduciary benefits include medical and educational services, the action of which is extended over time and is quite difficult to identify. Institutions whose coordination effect is practically impossible to measure can also be considered as trust benefits.

The already mentioned institution of advertising is a factor that reduces not only the costs of searching for information, but also the transaction costs of measurement. Because, firstly, advertising provides information about the main ways to use the product. Secondly, the amount of advertising related to the empirical quality of the product serves as a signal to the buyer about the scale of investment made by the seller. Assuming that advertising cannot change tastes, large-scale advertising indicates a manufacturer's commitment to providing high-quality products.

Note that the last assumption is unprovable. Rather, in modern conditions advertising is primarily aimed at changing tastes, being an instrument for implementing the principle “create demand and satisfy it,” in contrast to the principle that prevails in the conditions of the models considered by neoclassical theory, where the behavior of producers comes down to finding existing demand from buyers and satisfying it.

As representatives of traditional institutionalism, in particular Veblen, emphasized, advertising is primarily a mechanism for exercising the power of the producer over the consumer and, to a much lesser extent, can be considered a way of reducing measurement costs and information search costs. Advertising in this capacity can be considered only if one accepts the postulate of an “economic” person, whose characteristic is independence (insuggestibility), i.e. accurate knowledge of the system of your true preferences. It is over such a person that advertising has no power and serves as a means of reducing the costs described above.

The institute of advertising becomes widespread with the formation of a mass consumption society, i.e. from the end of the 19th century Let us note that in traditional societies, as in the early stages of the formation of a market economy, advertising was categorically condemned, since it was viewed as a tool of competition, leading to the destruction of social ties and norms of economic interaction.

If we look at the problem from a historical perspective, then the institutional response to the costs of measurement was not advertising, but a system of weights and measures. The latter made different quantities of goods comparable, thereby significantly facilitating exchange and ensuring enormous savings in measurement costs. By the way, money can also be interpreted as an institutional reaction to the problem of barter exchange, where money acts as a generally accepted means of payment, protected either by tradition, economic custom, or by the power of the state. Here, money is a means of reducing transaction costs associated with measuring the quality of the good being exchanged, as well as finding a partner who has the right product.

In addition to information search costs and measurement costs, an important element of transaction costs is negotiation costs.

It is obvious that developing the terms of a contract designed to give stability to relationships requires both time resources and the diversion of significant funds to negotiate the terms of exchange, to conclude and formalize the contracts themselves. A tool for reducing costs of this kind is the standardization of contracts, if the situations that are regulated by these contracts are typical in terms of the mutual obligations of the parties. In addition, to reduce the costs of concluding a contract, a third party is used as a guarantor, which can partly compensate for the lack of mutual trust of the parties.

However, the most hidden and, from the point of view of neo-institutional economic theory, the most interesting element of transaction costs are the so-called costs of opportunistic behavior. The term “opportunistic behavior” itself was introduced into economic theory by a prominent representative of the neo-institutional movement, O. Williamson, who interprets it as behavior that evades the terms of the contract. This includes various cases of lying, deceit, loafing at work, etc. In this case, it is taken as an axiom that utility maximizing individuals will always deviate from the terms of the contract (i.e., provide less services or worse quality) to the extent that it does not threaten them economic security. Thus, the costs of opportunistic behavior are reduced to the costs of preventing this type of behavior.

And finally, transaction costs include costs of specification and protection of property rights. It has already been noted that benefits have many dimensions, including from the point of view of possible ways of their use, therefore certain resources are required to clearly define the object and subject of property rights. The problem of specification of property rights arises almost everywhere if a system of interaction between people regarding limited resources is reproduced. This includes costs associated with protecting concluded contracts from non-fulfillment, as well as from attacks on property rights by third parties.

In this case, protection can be carried out both by the parties to the contract themselves, and by a party neutral in relation to them, acting as a fair, impartial arbiter. As already noted, the state came to play this role in the process of historical development. And, naturally, this category of transaction costs includes the costs of maintaining courts, arbitration, and government bodies. This also includes the expenditure of time and resources necessary to restore violated rights.

Some authors, in particular D. North, add here the costs of maintaining a consensus ideology in society, since educating members of society in the spirit of observing generally accepted unwritten rules and ethical standards is a much more economical way to protect property rights than formalized legal control. In such a broad interpretation, this type of costs includes not only costs associated with the direct protection of property rights, an essential element of which are the costs of maintaining law enforcement agencies, but partly also costs in the field of education. The latter is true to the extent that this sphere ensures that people are informed about the existing social and legal conditions of exchange and forms behavior that determines the appropriate fulfillment of obligations.

This classification of transaction costs is the most common and concerns mainly trade transactions. Which is not surprising, since within the framework of neo-institutional analysis, the voluntariness of the transaction, which is main characteristic namely trade transactions.

However, there are other classifications of transaction costs. In particular, in O. Williamson’s interpretation they are divided into two groups: preliminary and final. This means classifying transaction costs according to the criterion of “transaction stages”.

The preliminary stages of the transaction include searching for transaction partners and coordinating their interests. The final stages of the transaction include the execution of the transaction and control over its implementation. The first type of costs is called “ex ante”, the second - “ex post”.

As a consequence, to "preliminary" transaction costs include:

- costs of searching for information, including information about a potential partner and the market situation, as well as losses associated with the incompleteness and imperfection of the acquired information;

- costs of negotiating the terms of exchange, choosing the form of the transaction;

- costs of measuring the quality of goods and services for which a transaction is made;

- costs of concluding a contract in the form of legal or illegal execution of the transaction.

TO "final" costs include:

- costs of monitoring and preventing opportunism (costs of monitoring compliance with the terms of the transaction and evasion of these conditions);

- costs of specification and protection of property rights (costs of maintaining courts and arbitration; costs of time and resources necessary to restore rights violated during the execution of the contract; losses from poor specification of property rights and unreliable protection);

- costs of protection from unfounded claims from third parties, for example mafia groups.

It is important to note that under the assumption of completeness of information, the activities that generate the above transaction costs would either be unnecessary or cost-free. In particular, the potential opportunistic behavior of exchange partners would be known in advance, and rational individuals would not devote resources to enforcement and enforcement of their contractual rights.

However, in the real world, information belongs to the category of rare, limited resources, and is therefore an economic good and is by no means free. It is no coincidence that one economist called a world with zero transaction costs as strange as a physical world without friction. It means that economic system also exists with some "friction" that makes economic exchanges difficult to carry out. This “friction” in the exchange of goods, which in neo-institutional theory is interpreted as an exchange of bundles of powers, gives rise to transaction costs, which are a positive value in the real economy, and quite high at that. Sometimes they can reach a level where an otherwise beneficial exchange may not take place.

Thus, it is the incompleteness of information that determines the existence of transaction costs, since the latter are, one way or another, associated with the costs of obtaining information about the exchange. In a figurative expression, transaction costs consist of those costs whose existence is impossible to imagine in the economy of R. Crusoe. That is, they represent costs above and beyond the own costs of production.

It is worth noting that it is precisely if there is completeness of information among participants in the economic process and zero transaction costs of exchange within the framework of a market system that would ensure optimal distribution of resources and maximum social welfare in accordance with the Pareto optimum.

The presence of transaction costs can lead (and does) to a number of negative consequences for economic development. As noted in the first lecture, they interfere with the process of market formation, and in some cases can completely block it, which creates obstacles to the implementation of the principle of comparative advantage that underlies trade, and therefore economic growth.

Their presence also makes it difficult to find new opportunities to use known resources or discover new resources. And, as we will see later, the presence of transaction costs prevents changes in the existing rules of the game, acting as costs of institutional transformation.

What makes it possible to reduce transaction costs? Last but not least is their ability to create economies of scale. This is due to the fact that there are constant components in all types of transaction costs: once information is collected, it can be used by any number of potential sellers and buyers; contracts are standardized; the cost of developing legislation or administrative procedures does not depend on the number of persons affected by them. And, once established, property rights can be extended almost indefinitely to other areas at little additional cost.

As a consequence, by saving transaction costs on the market scale, the per capita income of the population can increase even in the absence of technical progress due to the growing “marketization” of the economy. The latter is caused precisely by a reduction in transaction costs accompanying exchange, and allows the benefits of division of labor or specialization to be realized.

Returning to the first lecture, let us once again draw attention to the fact that in neo-institutional economic theory the formation of market economy institutions is considered as a process leading to a reduction in transaction costs (or exchange costs). Transaction costs are generated by incomplete information, or uncertainty in conditions of divergence of interests of economic agents interacting with each other, and therefore the existing set of institutions in society, according to representatives of the neo-institutional movement, is advisable to analyze from the point of view of their influence on these problems.

As we see, transaction costs are one of the central categories of neo-institutional theory. Including them in economic analysis allows us to explain almost all phenomena in terms of efficiency achieved by minimizing transaction costs. But it is worth paying attention to the fact that they are based on components invisible to the naked eye and are difficult to quantify. And at the same time, transaction costs are, within the framework of neo-institutional analysis, the key to understanding the processes occurring in the economy.

Given the importance of this category, it is not surprising that attempts have been made to develop methods for estimating transaction costs. One approach is to clearly specify costs on a case-by-case basis. In one case, for example, these may be the costs of entering the market (registering a company, obtaining a license), in another - the costs associated with concluding and protecting contracts, etc. When broken down element by element, many components of these costs turn out to be quite measurable.

A slightly different approach is indicated by the American economists J. Wallis and D. North: the basis of the analysis is the distinction they introduced between “transformation” (related to the physical impact on the object) and transaction costs. In their opinion, transformation costs are the costs associated with converting resources into finished products. To determine transaction costs, the following criterion is used: from the consumer’s point of view, these costs are all his expenses, the cost of which is not included in the price he pays to the seller; From the seller's point of view, these costs are all his costs that he would not incur if he were “selling” the product to himself.

Developing this approach, these economists tried to determine the size of the so-called transaction sector in the US economy, or the share of transaction costs relative to GNP and its development trends. The calculation was made on the basis of determining the total amount of resources used by firms selling transaction services, as well as measuring the resources allocated to transaction services by firms producing other goods and services.

This classification made it possible to identify a special category of firms whose activities are related to the provision of transaction services. And even if transformation costs occur within the framework of their activities, then at the level of the economy as a whole, according to the above-mentioned economists, they are still assessed as part of transaction costs. This category of firms includes intermediaries that provide pure transaction services or primarily transaction services. Taken together, they represent transaction industries. North and Wallis included groups of firms operating in the following areas:

- finance and real estate transactions. The main function of these companies is to ensure the transfer of property rights, including the search for alternatives, preparation and support of transactions;

- banking and insurance. Their main function is to mediate exchanges and reduce costs associated with the security of realizing property rights to the corresponding resource;

- legal or legal services. The main function of the relevant organizations is to ensure coordination and control of the implementation of contract terms. For example, firms hire lawyers in order to save on the costs of using the existing system of rules, since it is difficult to take into account the various regulations that constitute the institutional environment of the firm;

- wholesale and retail. Of course, it includes both transactional and transformational services, which include storage. However, in the study of the above-mentioned economists, it was treated as a transactional industry.

North and Wallis also included government services and intra-company transaction services in the transaction sector of the economy. Transaction services in the public or public sector include: national defense, police, air and water transport, financial management And general control; education, healthcare, highway maintenance, fire protection, etc.; other expenses (social insurance, space research, etc.).

As a result of the study, it was revealed that the growth of the transaction sector of the US economy amounted from a quarter of GNP in 1870 to half in 1970. At the same time, North and Wallis identified three main factors for the expansion of the transaction sector of the economy.

First of all - rising costs of specification and protection of property rights, maintaining contractual relations. This is not surprising, since with the development of market relations, accompanied by increased specialization and urbanization, exchange is increasingly becoming impersonal, depersonalized, which requires the widespread use of legal specialists. In addition, the expansion of the sphere of exchange, increasing the range of possible alternatives, also led to an increase in the costs of obtaining and processing information.

Second factor - technological changes. Capital-intensive technologies can be used profitably if they can achieve consistently high levels of output. And for this it is necessary to establish both the provision of a rhythmic, uninterrupted supply of resources and the creation of a system for managing inventories and sales of manufactured products, as well as the creation of a system that ensures coordination and control over the actions of people within the company. Thus, these processes have led to an increase in the share of intra-company transaction services in the transformation sector of the economy.

Third factor - reducing the costs of using the political system to redistribute property rights.

In other words, the factors that caused the growth of the transaction sector, according to North and Wallis, were:

- deepening specialization and division of labor, increasing the number of transactions concluded;

- increasing the scale of enterprises in industry and transport;

- strengthening the role and influence of the state.

The sharp increase in the transaction sector, according to these economists, began in the middle of the 19th century. in connection with the development of the network railways, which paved the way for the urbanization of the population and the expansion of markets. And, as already noted, it was this process that was accompanied by the growth of impersonal exchange, requiring a detailed definition of the terms of the transaction and developed legal protection mechanisms. At the same time, the consequences of greater product diversity and weakening personal contacts were expressed in the fact that economic agents increased their expenses for searching and processing market information, which led to the creation of specialized structures.

At the same time, and this should be emphasized, the share of transaction costs per transaction has decreased significantly. And it is quite convincing to assume that, ultimately, the development of the transaction sector was due precisely to the fact that the accompanying reduction in costs per transaction opened the way for a further deepening of specialization and division of labor.

In conclusion, we note that North and Wallis's study only takes into account specified transaction costs. And this indirectly indicates that accounting for transaction costs becomes possible when transaction activities move into the sphere of transaction services. In this case, it becomes possible to give them a generalized cost estimate. As an example, turnkey delivery of companies, cash withdrawals, recruiting services. At the same time, a number of costs that should be classified as unspecified transaction costs, such as waiting in queues and costs of searching for goods, remained outside the field of view of researchers.

However, despite all the difficulties in calculating them, within the framework of neo-institutional analysis, transaction costs become an element of the costs of economic activity along with transformation costs, which are the object of analysis in traditional neoclassical theory. Moreover, it is precisely by relative differences in the levels and structure of transaction costs that representatives of neo-institutionalism explain all the diversity of forms of economic and social life. Alternative economic institutions are said to have comparative advantages in saving on different categories of transaction costs and their coexistence is due precisely to this.

This approach is clearly presented in theory economic organizations, and in the theory of contracts, the analysis of which is devoted to the next lecture.

- One of the problems that arises here, which is called the “information paradox,” is precisely that it is quite difficult to give a preliminary assessment of the significance of the information received. There are other approaches, and if we take as a criterion the area in which transaction costs arise, we can distinguish: market transaction costs - for searching and processing information associated with negotiations, decision-making and monitoring their implementation; management transaction costs - costs of development, implementation and maintenance organizational structure; political transaction costs - costs of creating, maintaining and changing the legal system, legal proceedings, defense, education, etc.

- As has been noted more than once, the premise of completeness of information (within the framework of the adoption of the model of “economic” man) is one of the basic ones in neoclassical models. In addition, any exchange is considered in them as a one-time exchange of rights, the benefit is researchable, the company is a monolith that excludes the existence of conflicting interests in it, i.e. absence of opportunistic behavior is assumed.

- And from the same positions, a criterion for their effectiveness is put forward. It has been repeatedly noted that this approach is rooted in a value system that assumes that the goal of economic development is the growth of the nation’s wealth, expressed in the totality of goods and services produced.

- For example, when buying a house, the buyer's transaction costs will include the cost of hiring a lawyer, time spent inspecting the house, and collecting information on prices for similar products. For the seller, such costs will consist of advertising costs, hiring a real estate agent, time spent showing the house, etc.

- To quantify the transaction sector within a company, North and Wallis proposed to identify professions that are directly related to the performance of transaction functions (these include activities related to: acquisition of resources; distribution of the manufactured product; coordination and control of the implementation of transformation functions); and the amount of transaction costs is determined by calculating the wages of those employed in the intra-company transaction sector.

Let us turn to the classification of transaction costs by Douglas North and Train Eggertson. It was first proposed by North, and clearly formulated by Eggertson in the book “Economic Behavior and Institutions”. This is a simple and clear classification. It is the only one built on the tangible external signs of a certain activity that generates corresponding costs. According to North and Eggertson, transaction costs consist of the following components:

1) Search costs. There are four types of costs that are associated with search:

Reasonable price;

High-quality information about available goods and services;

High-quality information about sellers;

High-quality information about buyers.

Quantitative information about sellers and buyers has already been given in the first two positions. Qualitative information about sellers and buyers means information about their behavior - whether they are honest, how they fulfill their obligations, what their circumstances are (maybe one of them is on the verge of collapse or, conversely, thriving);

2) Negotiation costs. In a market sense, you bargain to minimize costs. During the negotiation process, you are looking for your partner’s limiting indifference curve (what price he can reach when trading). After all, each of those trading has both a certain asking price and a certain reserve price. During the negotiation process, you try in different ways to get as close as possible to the maximum - the lowest or highest - price that your partner is able to give. Those. negotiations lead to the clarification of the so-called “true position”, which in the economic sense is a marginal indifference curve or a marginal isoquant (in the case of a company). What costs and expenses do you incur in negotiations?

If you are individually bargaining with someone at the market, you waste time saying that it is expensive for you, that you have little money, hinting that you are a wonderful object for a policy of price discrimination, turn around, leave, demonstratively approach another stall .

What are the company's costs in the negotiation process?

It should be noted that search costs and negotiation costs are fundamentally different things. During the search process, you have not yet identified partners, you are just selecting them. By the way, you are engaged in such activities on the Internet (in fact, this is browsing, preferably with minimal costs). And negotiations assume that you have identified a narrow circle of your partners - one, two or three - and are already negotiating with them (negotiations are expensive, so there is no point in conducting them with everyone).

Your costs as a firm in the negotiation process can be very significant if you organize a tender. For example, the European Commission takes 15% of the transaction amount as a fee to the tender agency. However, the costs will not necessarily be great if you manage to buy someone in the “enemy” camp in order to find out the partner’s backup position. To do this, in our conditions, with a low economic culture and low resilience, sometimes it is enough to take your partner’s representative to a good restaurant, and over dinner he will simply let it slip. This same way of obtaining information is very often used in the West. In fact, the costs of negotiations formally include representation expenses for negotiations. The latter have a very specific function: they must find out the true position of the partner.

3) Costs of drawing up a contract. These are your costs for ensuring that the text of the contract records how in certain cases (foreseen by you) your partner will behave and how external circumstances will develop. And in relation to cases that you have not foreseen, a certain mechanism is usually formulated in the contract. Let's say, it is established: if we do not agree, we will be judged by the International Arbitration Court of Stockholm (the usual authority for international contracts). Those. a certain position is specifically reserved for unforeseen circumstances. The costs of drawing up a contract are among the most expensive (5-10% of the transaction volume) when investing in specific assets. This is fantastic money! But in some cases the risks are so great, the responsibility for what is written in the contract is so great that you are forced to spend it on lawyers.

4) Monitoring costs. Points 1-3 related to activities ex ante (before the appearance of a legally formalized contract). And from point 4, when such a contract has already appeared, ex post activity begins (after its appearance). And it begins with monitoring the execution of the contract by each of the counterparties.

For example, having bought a car, you within warranty period You can have it repaired at the seller’s expense at a service station - this will be the cost of monitoring when purchasing the car. And after the expiration of the warranty period, certain monitoring can also take place, but not within the framework of the first transaction (it is already completed), but in the case when you want to continue relations with this supplier, so that in a 5-year perspective you can buy another one from him again car.

Another example. You ordered a plane from the Tashkent Aviation Plant, signed everything necessary papers, they transferred part of the money to the plant, and they began making the plane. In this case, the emergence of the institution of customer representatives will be associated with monitoring: you will send your representative to this aircraft plant, and although such a business trip is quite expensive, in comparison with the volume of the transaction itself it is insignificant.

Note that not all monitoring costs are borne by the buyer. Some of them are also profitable for the seller. A classic example of monitoring from the manufacturer is the automotive industry. You can regularly read that, say, Ford has recalled all its models of certain years of production. Those. the company, in an effort not to lose its name and position in the market, itself monitors cases of severe accidents, tracking how its products work, which entails considerable costs for it.

5) Coercion costs. These are the costs of forcing the other party to fulfill the terms of the contract. Because people seek to act in their own best interests and information is (by definition) incomplete, situations often arise where a contract is not fulfilled in part or in full. It is assumed that there is a system that forces partners to comply with the terms of the contract. Such a system is primarily the state, and also to some extent professional associations and the private legal system. The latter interacts with the previous two, complementing them. But there is also an alternative system of coercion that arises in a weak state and competes with it. This is a private system of coercion. This includes the mafia, all kinds of “roofs”, etc.

Let us emphasize that the lion's share of the costs of enforcing contracts in normal civilized economies is free for economic agents. These are costs for the state, and it saves on scale. After all, it is expensive for each of us to search for and constantly maintain a bailiff or a “man with a gun.” The state, taking into account that such cases regularly arise, contains and arbitration courts, and ordinary criminal courts, and the system of threats of violence - the prison system, the system of judicial agents, etc. Naturally, the system of coercion is financed to a huge extent by the state (through taxes, roughly speaking, since there is no such thing as a free state).

6) Costs of protecting property rights. This is the only static form of transaction cost, as opposed to the dynamic costs associated with securing contracts.

For example, you planted potatoes 100 km from Moscow for your own consumption, and not for sale, but homeless people dig them up. You either fold with your neighbors and hire a man with a gun loaded with salt for security, or refuse to plant potatoes at all, or lose up to 60% of the harvest. Both, and the other, and the third are specific either positive or negative transaction costs associated with the protection of property rights.

Basic provisions

Definition 1

Let's consider the concept of transaction costs, which is understood as the costs that arise when using market mechanisms and are associated with concluding contracts.

In practice, there are many approaches to classify this type costs This is due to the fact that there are also many different views on considering the essence and problem of transaction costs.

Let's consider the approaches of various scientists and researchers.

Classification according to O. Williamson

It is customary to distinguish two main groups of costs, which are called in English as:

- ex ante;

- ex post.

The first group usually includes the costs of compiling specific project, agreement, conduct the necessary negotiations.

The second group of costs involves direct costs aimed at organization and operating costs. Here the costs will be associated with the specifics of management, adaptation, legal costs, costs associated with unforeseen events, costs that arise during the execution of the contract.

Classification according to K. Menard

In this approach, more groups are distinguished. It is customary to classify the costs under consideration into 4 main groups:

- costs of isolating (or shirking);

- costs of scale;

- costs associated with information flows;

- costs associated with behavioral characteristics.

In any operating company, the problem of inseparability arises. It is assumed that it is not possible to accurately determine the productivity per unit of each factor that is involved in production activities, nor, under such conditions, to accurately calculate remuneration.

The next type of costs assumes that the larger the volume and scale of the market, the more impersonal exchange flows become. Therefore, it is important to develop institutional mechanisms that consider the different natures of contracts, monitor compliance with the laws of countries, control, and impose sanctions in case of violation of the law.

The third group is information costs. Since all transactions are related to information, information systems and databases, then this group include such costs as the scope of information functioning, that is, coding, user training, and the price of transmitting information via communication channels.

The fourth group involves costs that arise from the selfish, opportunistic behavior of counterparties when concluding contracts.

Classification according to R. Kapelyushnikov

This classification is more common and well-known. Let's take a closer look:

- costs associated with searching for various necessary information;

- costs incurred during negotiations with counterparties (for example, creating the necessary conditions for negotiations, requirements of counterparties to the terms of negotiations, emerging costs for conducting such negotiations);

- the costs of measuring accuracy (arise in a situation where, in acts of exchange, the quality of a product may be immeasurable or expressed through other measurements). Therefore, there are, for example, costs for additional measuring equipment;

- specification costs;

- costs associated with protecting property rights;

- opportunistic costs (incur moral hazard, failure to fulfill contract terms).

- In general, this classification of transaction costs is broader and more general.

Examples of different types of transaction costs from the classifications are presented in the figure.

It should be noted that today there is no generally accepted classification of transaction costs. Each of the researchers paid attention to the most interesting, from his point of view, elements. For example, Stigler J. identified among them “information costs”, Williamson O. – “costs of opportunistic behavior”, Jensen M. and Meckling U. – “costs of monitoring the agent’s behavior and the costs of his self-restraint”, Barzel J. – “measurement costs ”, Milgrom P. and Roberts J. - “costs of influence”, Hansmann G. - “costs of collective decision-making”, and Dalman K. included in their composition “costs of collecting and processing information, costs of negotiations and decision-making, costs of control and legal protection of contract performance.” Let's consider Menard's classification.

Menard Cl. identifies four types of transaction costs:

Isolation costs caused by varying degrees of technological divisibility of production operations (similar to the costs of shirking);

Information costs, including encoding costs, signal transmission costs, decoding costs and training costs to use the information system;

The costs of scale are due to the existence of systems of impersonal exchange, requiring a system for enforcing contracts;

Costs of opportunistic behavior.

In the functioning of any organization, there is, first of all, the problem of inseparability, and the total costs of separation arise precisely for this reason. In most cases, economic activity is driven by cooperative efforts, and it is impossible to accurately measure the marginal productivity of each factor involved and its reward. K. Menard gives the example of a team of loaders: “To set the wages of the team, using the organization turns out to be more effective than using the market. The organization surpasses the market even when the latter requires too detailed, otherwise impossible, differentiation.”

Further, K. Menard highlights the costs of scale. The larger the scale of the market, the more impersonal the acts of exchange are, and the more necessary it is to develop institutional mechanisms that determine the nature of the contract, the rules for its application, sanctions for non-compliance with obligations, etc. The establishment of employment contracts designed to stabilize the relationship between employer and employee, supply contracts to ensure the regularity of the flow of costs, is partly explained by the need to establish “trust, which the scale of markets and periodic contracting would make both problematic and expensive.”

Information costs represent a separate category. The transaction is associated with an information system, the role of which in the modern economy is played by the price system. This category includes costs that cover all aspects of the functioning of an information system: coding costs, signal transmission costs, training costs to use the system, etc. Every system, through its functioning, creates various interferences, which reduce the accuracy of price signals. The latter cannot be too differentiated, since the manipulation of a very large number of signals is associated with prohibitive costs. The organization in this case allows you to reduce costs by using less of the market and limiting the number of signals sent and received.”

The last group consists of behavioral costs. They are associated with “selfish behavior of agents”; a similar concept accepted and used now is “opportunistic behavior.”

1.4. North–Eggertsson cost classification

In Douglas North's interpretation, transaction costs “consist of the costs of assessing the useful properties of the object of exchange and the costs of ensuring rights and enforcing their observance.” These costs inform social, political, and economic institutions.

Let's consider the North-Eggertson classification of transaction costs, according to which transaction costs consist of the following main classes:

· Activities ex ante (activities before a legally formalized contract appears):

Search activities (search costs)

Bargaining activities

Contract making activities

· Activities ex post (activities after the appearance of the contract):

Monitoring (monitoring costs)

Enforcement (costs of coercion)

Protection vs 3d parties (costs of protecting property rights)

Let's look at some of them in more detail.

Search costs are associated with information search, which is carried out not only using information retrieval systems, but in all possible ways, including information intelligence.

This class includes costs associated with incompleteness (uncertainty, vagueness) of information and the need for its additional collection. Limited information about the market may lead to refusal to complete a transaction. When the level of information uncertainty becomes high, economic agents prefer to abandon active actions rather than spend resources on obtaining additional information.

In class and Negotiation costs include coordination and motivational costs. Coordination costs, in turn, are divided into three types:

1) Costs of determining the details of the contract. Essentially, it is a market survey to determine what is generally available in the market before you narrow your approach to anything specific.

2) Costs of identifying partners. These costs are associated with exploring possible partners who provide the desired services or products.

3) Costs of direct coordination. These costs arise when concluding a complex contract, when it becomes necessary to create some kind of joint structure or system within which the parties are brought together and the transaction itself is carried out. This system includes the contractor, the customer and agents representing their interests. Such agents may be trustees, lawyers, brokers expediting the transaction, an intermediary firm, etc.

Motivational costs- costs associated with the selection process: to enter into or not to enter into a given contract. Costs of determining contract details. These costs arise at the first stage in order to determine whether a contract is worth entering into before making a specific decision about its content.

AND Negotiation delays are associated with loss of time during bidding, searching for the necessary information for bidding, and acquiring the necessary information for bidding. This all also leads to costs. Therefore, the bidder, in the process of negotiations, looks for the partner’s limiting indifference curve (what price he can reach when trading).

Each bidder has a certain asking price and a certain reserve price. In the process of negotiations, one of the bargaining partners tries in different ways to get as close as possible to the limit - the lowest or highest - price that the other partner is able to give. Hence, the costs of negotiations lead to finding the marginal indifference curve.

It should be noted that search costs and negotiation costs are significantly different. During the search process, partners are not identified and are selected. An example of such an activity is Internet searching. Negotiations presuppose that the circle of partners has been determined. Negotiations are conducted only with them, so there is no point in conducting them with everyone. The company's costs in the negotiation process can be significant if a tender is organized. For example, the European Commission takes 15% of the transaction amount as a fee to the tender agency. However, the costs will not necessarily be high if information intelligence methods can be used to find out the partner’s backup position. Therefore, expenses of this kind include representation expenses for negotiations.

AND The costs of drawing up a contract are associated with ensuring that the text of the contract records how in certain possible (foreseen) cases the executor of the contract (partner) will behave and how external circumstances will develop. Since it is impossible to provide for all cases, a certain mechanism is formulated in the contract in relation to such cases. For example, a condition is established that in the absence of an agreement on the delivery and acceptance of products, controversial issues will be resolved by a local arbitration or other court (for example, the International Court). This condition reserves some position for unforeseen circumstances. AND Contract drafting costs are among the most expensive (5-10% of the transaction volume) when investing in specific assets. Although this is a lot of money, in some cases the risks are so great that they are forced to spend it on lawyers.

Information monitoring costs arise when the contract has already been signed. The essence of these costs is related to monitoring the execution of the contract by each of the counterparties. Not all monitoring costs are made by the customer (buyer).

AND Enforcement costs are the costs of forcing the other party to comply with the terms of the contract. They arise because the information in the contract is (by definition) incomplete and situations often arise where the contract is not fulfilled in part or in full. To eliminate such situations, the costs of engaging third-party experts to identify inaccuracies and adjust the contract are necessary.

There may be cases of non-fulfillment of obligations even within the framework of a clearly written task, but, for example, due to overspending by the contractor.